Understanding Metering and Metering Modes

Every modern DSLR has something called “Metering Mode”, also known as “Camera Metering”, “Exposure Metering” or simply “Metering”. Knowing how metering works and what each of the metering modes does is important in photography, because it helps photographers control their exposure with minimum effort and take better pictures in unusual lighting situations. In this understanding metering modes article, I will explain what metering is, how it works and how you can use it for your digital photography.

When I got my first DSLR (Nikon D80), one of my frustrations was that some images would come out too bright or too dark. I had no idea how to fix it, until one day, when I learned about camera metering modes.

1) What is Metering?

Metering is how your camera determines what the correct shutter speed and aperture should be, depending on the amount of light that goes into the camera and the sensitivity of the sensor. Back in the old days of photography, cameras were not equipped with a light “meter”, which is a sensor that measures the amount and intensity of light. Photographers had to use hand-held light meters to determine the optimal exposure. Obviously, because the work was shot on film, they could not preview or see the results immediately, which is why they religiously relied on those light meters.

Today, every DSLR has an integrated light meter that automatically measures the reflected light and determines the optimal exposure. The most common metering modes in digital cameras today are:

- Matrix Metering (Nikon), also known as Evaluative Metering (Canon)

- Center-weighted Metering

- Spot Metering

Some Canon EOS models also offer “Partial Metering”, which is similar to Spot Metering, except the covered area is larger (approximately 8% of the viewfinder area near the center vs 3.5% in Spot Metering).

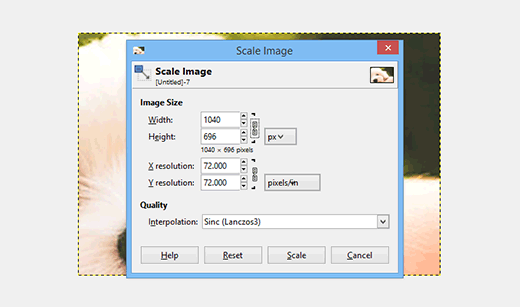

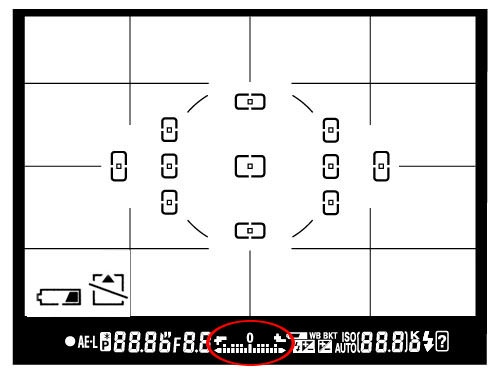

You can see the camera meter in action when you shoot in Manual Mode – look inside the viewfinder and you will see bars going left or right, with a zero in the middle, as illustrated below.

If you point your camera at a very bright area, the bars will go to “+” side, indicating that there is too much light for the current exposure settings. If you point your camera at a very dark area, the bars will go to the “-” side, indicating that there is not enough light. You would then need to increase or decrease your shutter speed to get to “0”, which is the optimal exposure, according to your camera meter.

A camera meter is not only useful for just the Manual Mode – when you choose another mode such as Aperture Priority, Shutter Priority or Program Mode, the camera automatically adjusts the settings based on what it reads from the meter.

1.1) Problems with Metering

Camera meters work great when the scene is lit evenly. However, it gets problematic and challenging for light meters to determine the exposure, when there are objects with different light levels and intensities. For example, if you are taking a picture of the blue sky with no clouds or sun in the frame, the image will be correctly exposed, because there is just one light level to deal with. The job gets a little harder if you add a few clouds into the image – the meter now needs to evaluate the brightness of the clouds versus the brightness of the sky and try to determine the optimal exposure. As a result, the camera meter might brighten up the sky a little bit in order to properly expose the white clouds – otherwise, the clouds would look too white or “overexposed”.

What would happen if you added a big mountain into the scene? Now the camera meter would see that there is a large object that is much darker (relative to the clouds and the sky), and it would try to come up with something in the middle, so that the mountain is properly exposed as well. By default, the camera meter looks at the light levels in the entire frame and tries to come up with an exposure that balances the bright and the dark areas of the image.

2) Matrix / Evaluative Metering

Matrix Metering or Evaluative Metering mode is the default metering mode on most DSLRs. It works similarly to the above example by dividing the entire frame into multiple “zones”, which are then all analyzed on individual basis for light and dark tones. One of the key factors (in addition to color, distance, subjects, highlights, etc) that affects matrix metering, is where the camera focus point is set to. After reading information from all individual zones, the metering system looks at where you focused within the frame and marks it more important than all other zones. There are many other variables used in the equation, which differ from manufacturer to manufacturer. Nikon, for example, also compares image data to a database of thousands of pictures for exposure calculation.

You should use this mode for most of your photography, since it will generally do a pretty good job in determining the correct exposure. I leave my camera metering mode on matrix metering for most of my photography needs, including landscape and portrait photography.

3) Center-weighted Metering

Using the whole frame for determining the correct exposure is not always desirable. What if you are trying to take a headshot of a person with the sun behind? This is where center-weighted metering comes in handy. Center-weighted Metering evaluates the light in the middle of the frame and its surroundings and ignores the corners. Compared to Matrix Metering, Center-weighted Metering does not look at the focus point you select and only evaluates the middle area of the image.

Use this mode when you want the camera to prioritize the middle of the frame, which works great for close-up portraits and relatively large subjects that are in the middle of the frame. For example, if you were taking a headshot of a person with the sun behind him/her, then this mode would expose the face of the person correctly, even though everything else would probably get heavily overexposed.

4) Spot Metering

Spot Metering only evaluates the light around your focus point and ignores everything else. It evaluates a single zone/cell and calculates exposure based on that single area, nothing else. I personally use this mode a lot for my bird photography, because the birds mostly occupy a small area of the frame and I need to make sure that I expose them properly, whether the background is bright or dark. Because the light is evaluated where I place my focus point, I could get an accurate exposure on the bird even when the bird is in the corner of the frame. Also, if you were taking a picture of a person with the sun behind but they occupied a small part of the frame, it is best to use the spot metering mode instead. When your subjects do not take much of the space, using Matrix or Center-weighted metering modes would most likely result in a silhouette, if the subject was back-lit. Spot metering works great for back-lit subjects like that.

Another good example of using spot metering is when photographing the Moon. Because the moon would take up a small portion of the frame and the sky is completely dark around it, it is best to use Spot metering – that way, we are only looking at the light level coming from the moon and nothing else.

Some DSLRs like the Canon 1D/1Ds are capable of multi-spot metering, which basically allows choosing multiple spots to measure light and come up with an average value for a good exposure.

5) How to Change Camera Metering Mode

Unfortunately, this varies not only from manufacturer to manufacturer, but also from model to model. On the Nikon D5500, for example, it is done through the menu setting (Info button). On professional cameras such as the Nikon D810 and Nikon D5, there is a separate button on the top left dial for camera metering. Changing metering on Canon cameras also varies from model to model, but generally it is done through a key combination (“Set” button), camera menu or a dedicated metering button close to the top LCD.

Source: https://photographylife.com/understanding-metering-modes