Music

Wolf Trap National Park for the Performing Arts

Hahn – Mozart – Violin Concerto No.3

Game of Thrones Piano Improvisation | Scott Bradlee

Mozart: Vesperae Solemnes de Confessore. Hogwood, the Academy of Ancient Music

Nana Mouskouri

Ioanna Mouschouri (Greek: Ιωάννα Μούσχουρη [ioˈana ˈmusxuri]; born October 13, 1934), known professionally as Nana Mouskouri (Greek: Νάνα Μούσχουρη [ˈnana ˈmusxuri]), is a Greek singer. During the span of her music career she has released over 200 albums and singles in at least twelve different languages, including Greek, French, English, German, Dutch, Italian, Portuguese, Spanish, Hebrew, Welsh, Mandarin Chinese and Corsican.[1][2][3][4]

Mouskouri became well-known throughout Europe for the song “The White Rose of Athens”, recorded first in German as “Weiße Rosen aus Athen” as an adaptation of her Greek song “Σαν σφυρίξεις τρείς φορές” (San sfyríxeis tris forés, “When you whistle three times”). It became her first record to sell over one million copies.[5]

Later in 1963, she represented Luxembourg at the Eurovision Song Contest with the song “À force de prier“. Her friendship with the composer Michel Legrand led to the recording by Mouskouri of the theme song of the Oscar-nominated film The Umbrellas of Cherbourg. From 1968 to 1976, she hosted her own TV show produced by BBC, Presenting Nana Mouskouri. Her popularity as a multilingual television personality and distinctive image, owing to the then unusual signature black-rimmed glasses, turned Mouskouri into an international star.

“Je chante avec toi Liberté“, recorded in 1981, is perhaps her biggest hit to date, performed in at least five languages[6] – French,[7] English as “Song for Liberty”,[8] German as “Lied der Freiheit”,[9] Spanish as “Libertad”[10] and Portuguese as “Liberdade”.[11] “Only Love“, a song recorded in 1985 as the theme song of tv-series Mistral’s Daughter, gained worldwide popularity along with its other versions in French (as “L’Amour en Héritage”), Italian (as “Come un’eredità”), Spanish (as “La dicha del amor”), and German (as “Aber die Liebe bleibt”). It became her only UK hit single when it reached number two in February 1986.[12][13]

Mouskouri became a spokesperson for UNICEF in 1993 and was elected to the European Parliament as a Greek deputy from 1994 to 1999.[14][15]

In 2015 she was awarded the Echo Music Prize for Outstanding achievements by the German music association Deutsche Phono-Akademie

Source: Nana Mouskouri – Wikipedia

Nana Mouskouri – Plaisir d’amour

ice is simply perfect for the ambiance and melody of the song. It’s an absolute ma

Gioachino Rossini – Largo Al Factotum (From the Opera “The Barber of Seville”) Lyrics

Largo al factotum della citta.

Largo! La la la la la la la LA!

Presto a bottega che l’alba e gia.

Presto! La la la la la la la LA!

Ah, che bel vivere, che bel piacere (che bel Piacere)

Per un barbiere di qualita! (di qualita!)

Bravo, bravissimo!

Bravo! La la la la la la la LA!

Bravo!

La la la la la la la LA!

Fortunatissimo per verita!

Fortunatissimo per verita!

La la la la, la la la la, la la la la la la la LA!

Sempre d’intorno in giro sta.

Miglior cuccagna per un barbiere,

Vita piu nobile, no, non si da.

La la la la la la la la la la la la la!

Lancette e forbici,

Al mio comando

Tutto qui sta.

Rasori e pettini

Lancette e forbici,

Al mio comando

Tutto qui sta.

Poi, de mestiere

Colla donnetta… col cavaliere…

Colla donnetta… la la li la la la la la

Col cavaliere… la la li la la la la la la la LA!!!

Per un barbiere di qualita! (di qualita!)

Donne, ragazzi, vecchi, fanciulle:

Qua la parruca… Presto la barba…

Qua la sanguigna… Presto il biglietto…

Tutto mi chiedono, tutti mi vogliono,

Tutti mi chiedono, tutti mi vogliono,

Qua la parruca, presto la barba, presto il biglietto,

Ehi!

Figaro… Figaro… Figaro… Figaro… Figaro!!!

Ahime, che folla!

Uno alla volta,

Per carita! (per carita! per carita!)

Uno alla volta, uno alla volta,

Uno alla volta, per carita!

Ehi, Figaro! Son qua.

Figaro su, Figaro giu, Figaro su, Figaro giu.

Sono il factotum della citta.

(della citta, della citta, della citta, della citta)

Ah, bravo Figaro! Bravo, bravissimo;

A te fortuna (a te fortuna, a te fortuna) non Manchera.

Ah, bravo Figaro! Bravo, bravissimo;

Ah, bravo Figaro! Bravo, bravissimo;

A te fortuna (a te fortuna, a te fortuna) non

Manchera.

Sono il factotum della citta,

Della citta, della citta,

Della citta!!!

La la la la la la la la la!

Ostinato

In music, an ostinato [ostiˈnaːto] (derived from Italian: stubborn, compare English, from Latin: ‘obstinate’) is a motif or phrase that persistently repeats in the same musical voice, frequently in the same pitch. Well-known ostinato-based pieces include both classical compositions such as Ravel‘s Boléro and the Carol of the Bells, and popular songs such as Donna Summer and Giorgio Moroder‘s “I Feel Love” (1977), Henry Mancini’s theme from Peter Gunn (1959), The Verve‘s “Bitter Sweet Symphony” (1997), and April Ivy‘s “Be Ok” (1997).

In RCM (Royal Conservatory of Music), a level 8 theory definition[clarification needed] for the term “ostinato” would be referred to as “a recurring rhythmic or melodic pattern”.[citation needed] The repeating idea may be a rhythmic pattern, part of a tune, or a complete melody in itself. Both ostinatos and ostinati are accepted English plural forms, the latter reflecting the word’s Italian etymology. Strictly speaking, ostinati should have exact repetition, but in common usage, the term covers repetition with variation and development, such as the alteration of an ostinato line to fit changing harmonies or keys.

If the cadence may be regarded as the cradle of tonality, the ostinato patterns can be considered the playground in which it grew strong and self-confident.

— Edward E. Lewinsky[5]

Within the context of film music, Claudia Gorbman defines an ostinato as a repeated melodic or rhythmic figure that propels scenes that lack dynamic visual action.

Ostinato plays an important part in improvised music (rock and jazz), in which it is often referred to as a riff or a vamp. A “favorite technique of contemporary jazz writers”, ostinati are often used in modal and Latin jazz and traditional African music including Gnawa music.

The term ostinato essentially has the same meaning as the medieval Latin word pes, the word ground as applied to classical music, and the word riff in contemporary popular music.

Source: Ostinato – Wikipedia

Inversion (music)

In music theory, the word inversion has distinct, but related, meanings when applied to intervals, chords, voices (in counterpoint), and melodies. The concept of inversion also plays an important role in musical set theory.

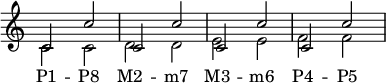

Intervals

An interval is inverted by raising or lowering either of the notes by one or more octaves so that the positions of the notes reverse (i.e. the higher note becomes the lower note and vice versa). For example, the inversion of an interval consisting of a C with an E above it (the third measure below) is an E with a C above it – to work this out, the C may be moved up, the E may be lowered, or both may be moved.

| Interval number under inversion |

||

|---|---|---|

| Unison | ↔ | Octave |

| Second | ↔ | Seventh |

| Third | ↔ | Sixth |

| Fourth | ↔ | Fifth |

| Interval quality under inversion |

||

|---|---|---|

| Perfect | ↔ | Perfect |

| Major | ↔ | Minor |

| Augmented | ↔ | Diminished |

The tables to the right show the changes in interval quality and interval number under inversion. Thus, perfect intervals remain perfect, major intervals become minor and vice versa, and augmented intervals become diminished and vice versa. (Doubly diminished intervals become doubly augmented intervals, and vice versa.).

Traditional interval numbers add up to nine: seconds become sevenths and vice versa, thirds become sixths and vice versa, and so on. Thus, a perfect fourth becomes a perfect fifth, an augmented fourth becomes a diminished fifth, and a simple interval (that is, one that is narrower than an octave) and its inversion, when added together, equal an octave. See also complement (music).

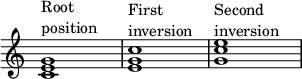

Chords

A chord‘s inversion describes the relationship of its lowest notes to the other notes in the chord. For instance, a C-major triad contains the tones C, E and G; its inversion is determined by which of these tones is the lowest note (or bass note) in the chord.

The term inversion often categorically refers to the different possibilities, though it may also be restricted to only those chords where the lowest note is not also the root of the chord. Texts that follow this restriction may use the term position instead, to refer to all of the possibilities as a category.

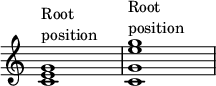

Root position and inverted chords

A chord is in root position if its root is the lowest note. This is sometimes known as the parent chord of its inversions.[citation needed] For example, the root of a C-major triad is C, so a C-major triad will be in root position if C is the lowest note and its third and fifth (E and G, respectively) are above it – or, on occasion, don’t sound at all.

The following C-major triads are both in root position, since the lowest note is the root. The rearrangement of the notes above the bass into different octaves (here, the note E) and the doubling of notes (here, G), is known as voicing – the first voicing is close voicing, while the second is open.

In an inverted chord, the root is not the lowest note. The inversions are numbered in the order their lowest notes appear in a close root-position chord (from bottom to top).

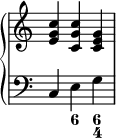

As shown above, a C-major triad (or any chord with three notes) has two inversions:

- In the first inversion, the lowest note is E – the third of the triad – with the fifth and the root stacked above it (the root now shifted an octave higher), forming the intervals of a minor third and a minor sixth above the inverted bass of E, respectively.

- In the second inversion, the lowest note is G – the fifth of the triad – with the root and the third above it (both again shifted an octave higher), forming a fourth and a sixth above the (inverted) bass of G, respectively.

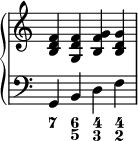

Chords with four notes (such as seventh chords) work in a similar way, except that they have three inversions, instead of just two. The three inversions of a G dominant seventh chord are:

Notating root position and inversions

Figured bass

| Triads | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Inversion | Intervals above bass |

Symbol | Example |

| Root position | 5 3 |

None |

|

| 1st inversion | 6 3 |

6 | |

| 2nd inversion | 6 4 |

6 4 |

|

| Seventh chords | |||

| Inversion | Intervals above bass |

Symbol | Example |

| Root position | 75 3 |

7 |

|

| 1st inversion | 65 3 |

6 5 |

|

| 2nd inversion | 64 3 |

4 3 |

|

| 3rd inversion | 64 2 |

4 2 or 2 |

|

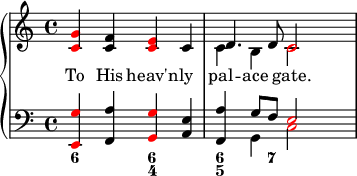

Figured bass is a notation in which chord inversions are indicated by Arabic numerals (the figures) either above or below the bass notes, indicating a harmonic progression. Each numeral expresses the interval that results from the voices above it (usually assuming octave equivalence). For example, in root-position triad C–E–G, the intervals above bass note C are a third and a fifth, giving the figures 5

3. If this triad were in first inversion (e.g., E–G–C), the figure 6

3 would apply, due to the intervals of a third and a sixth appearing above the bass note E.

Certain conventional abbreviations exist in the use of figured bass. For instance, root-position triads appear without symbols (the 5

3 is understood), and first-inversion triads are customarily abbreviated as just 6, rather than 6

3. The table to the right displays these conventions.

Figured-bass numerals express distinct intervals in a chord only as they relate to the bass note. They make no reference to the key of the progression (unlike Roman-numeral harmonic analysis), they do not express intervals between pairs of upper voices themselves – for example, in a C–E–G triad, the figured bass does not signify the interval relationship between E–G, they do not express notes in upper voices that double, or are unison with, the bass note.

However, the figures are often used on their own (without the bass) in music theory simply to specify a chord’s inversion. This is the basis for the terms given above such as “6

4 chord” for a second inversion triad. Similarly, in harmonic analysis the term I6 refers to a tonic triad in first inversion.

Popular-music notation

A notation for chord inversion often used in popular music is to write the name of a chord followed by a forward slash and then the name of the bass note.[4] This is called a slash chord. For example, a C-major chord in first inversion (i.e., with E in the bass) would be notated as “C/E”. This notation works even when a note not present in a triad is the bass; for example, F/G is a way of notating a particular approach to voicing a Fadd9 chord (G–F–A–C). This is quite different from analytical notations of function; e.g., the notation “IV/V” represents the subdominant of the dominant.

Lower-case letters

Lower-case letters may be placed after a chord symbol to indicate root position or inversion.[5][page needed] Hence, in the key of C major, a C-major chord in first inversion may be notated as Ib, indicating chord I, first inversion. (Less commonly, the root of the chord is named, followed by a lower-case letter: Cb). If no letter is added, the chord is assumed to be in root inversion, as though a had been inserted.

History

In Jean-Philippe Rameau‘s theory, chords in different inversions are considered functionally equivalent. However, theorists before Rameau spoke of different intervals in different ways, such as the regola delle terze e seste (“rule of sixths and thirds”), which requires the resolution of imperfect consonances to perfect ones and would not propose a similarity between 6

4 and 5

3 sonorities, for instance.

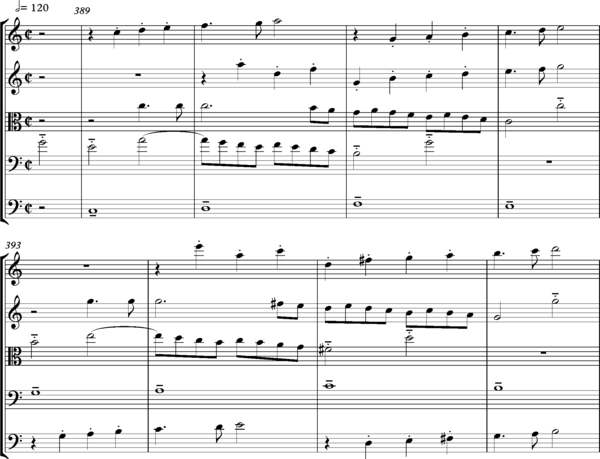

Counterpoint

In contrapuntal inversion, two melodies, having previously accompanied each other once, accompany each other again but with the melody that had been in the high voice now in the low, and vice versa. The action of changing the voices is called textural inversion. This is called double counterpoint when two voices are involved and triple counterpoint when three are involved. The inversion in two-part invertible counterpoint is also known as rivolgimento.[6]

Invertible counterpoint

Themes that can be developed in this way without violating the rules of counterpoint are said to be in invertible counterpoint. Invertible counterpoint can occur at various intervals, usually the octave, less often at the tenth or twelfth. To calculate the interval of inversion,[clarification needed] add the intervals by which each voice has moved and subtract one. For example: If motif A in the high voice moves down a sixth, and motif B in the low voice moves up a fifth, in such a way as to result in A and B having exchanged registers, then the two are in double counterpoint at the tenth (6 + 5 – 1 = 10).

In J.S. Bach‘s The Art of Fugue, the first canon is at the octave, the second canon at the tenth, the third canon at the twelfth, and the fourth canon in augmentation and contrary motion. Other exemplars can be found in the fugues in G minor and B♭ major [external Shockwave movies] from J.S. Bach’s The Well-Tempered Clavier, Book 2, both of which contain invertible counterpoint at the octave, tenth, and twelfth.

Examples

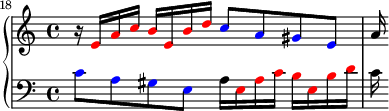

For example, in the keyboard prelude in A♭ major from J.S. Bach’s The Well-Tempered Clavier, Book 1, the following passage, from bars 9–18, involves two lines, one in each hand:

When this passage returns in bars 26–35 these lines are exchanged:

J.S. Bach’s Three-Part Invention in F minor, BWV 795 involves exploring the combination of three themes. Two of these are announced in the opening two bars. A third idea joins them in bars 2–4. When this passage is repeated a few bars later in bars 7–9, the three parts are interchanged:

The piece goes on to explore four of the six possible permutations of how these three lines can be combined in counterpoint.

One of the most spectacular examples of invertible counterpoint occurs in the finale of Mozart’s Jupiter Symphony. Here, no less than five themes are heard together:

The whole passage brings the symphony to a conclusion in a blaze of brilliant orchestral writing. According to Tom Service:

Mozart’s composition of the finale of the Jupiter Symphony is a palimpsest on music history as well as his own. As a musical achievement, its most obvious predecessor is really the fugal finale of his G major String Quartet K. 387, but this symphonic finale trumps even that piece in its scale and ambition. If the story of that operatic tune first movement is to turn instinctive emotion into contrapuntal experience, the finale does exactly the reverse, transmuting the most complex arts of compositional craft into pure, exhilarating feeling. Its models in Michael and Joseph Haydn are unquestionable, but Mozart simultaneously pays homage to them – and transcends them. Now that’s what I call real originality.[7]

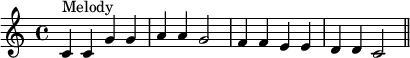

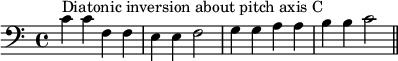

Melodies

A melody is inverted by flipping it “upside-down”, reversing the melody’s contour. For instance, if the original melody has a rising major third, then the inverted melody has a falling major third (or, especially in tonal music, perhaps a falling minor third).

According to The Harvard Dictionary of Music, “The intervals between successive pitches may remain exact or, more often in total music, they may be the equivalents in the diatonic scale. Hence c’–d–e’ may become c’–b–a (where the first descent is by a semitone rather than by a whole tone) instead of c’–b♭–a♭.”[8] Moreover, the inversion may start on the same pitch as the original melody, but it doesn’t have to, as illustrated by the example to the right.

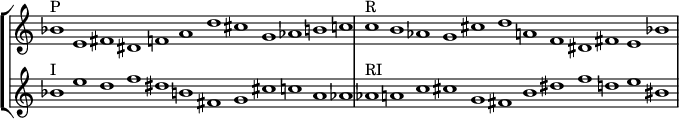

Twelve-tone music

In twelve-tone technique, the inversion of a tone row is one of its four traditional permutations (the others being the prime form, the retrograde, and the retrograde inversion). These four permutations (labeled Prime, Retrograde, Inversion, and Retrograde Inversion) for the tone row used in Arnold Schoenberg‘s Variations for Orchestra, Op. 31 are shown below.

In set theory, the inverse operation is sometimes designated as T n I {\displaystyle T_{n}I} , where I {\displaystyle I} means “invert” and T n {\displaystyle T_{n}} means “transpose by some interval n {\displaystyle n} ” measured in number of semitones. Thus, inversion is a combination of an inversion followed by a transposition. To apply the inversion operation I {\displaystyle I} , you subtract the pitch class, in integer notation, from 12 (by convention, inversion is around pitch class 0). Then we apply the transposition operation T n {\displaystyle T_{n}} by adding n {\displaystyle n} . For example, to calculate T 5 I ( 3 ) {\displaystyle T_{5}I(3)} , first subtract 3 from 12 (giving 9) and then add 5 (giving 14, which is equivalent to 2). Thus, T 5 I ( 3 ) = 2 {\displaystyle T_{5}I(3)=2} .[9] To invert a set of pitches, simply invert each pitch in the set in turn.[10]

Inversional equivalency and symmetry

Set theory

In set theory, inversional equivalency is the concept that intervals, chords, and other sets of pitches are the same when inverted.[citation needed] It is similar to enharmonic equivalency, octave equivalency and even transpositional equivalency. Inversional equivalency is used little in tonal theory, though it is assumed that sets that can be inverted into each other are remotely in common. However, they are only assumed identical or nearly identical in musical set theory.

Sets are said to be inversionally symmetrical if they map onto themselves under inversion. The pitch that the sets must be inverted around is said to be the axis of symmetry (or center). An axis may either be at a specific pitch or halfway between two pitches (assuming that microtones are not used). For example, the set C–E♭–E–F♯–G–B♭ has an axis at F, and an axis, a tritone away, at B if the set is listed as F♯–G–B♭–C–E♭–E. As another example, the set C–E–F–F♯–G–B has an axis at the dyad F/F♯ and an axis at B/C if it is listed as F♯–G–B–C–E–F.[11]

Jazz theory

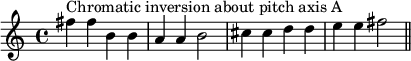

In jazz theory, a pitch axis is the center around which a melody is inverted.[12]

The “pitch axis” works in the context of the compound operation transpositional inversion, where transposition is carried out after inversion. However, unlike in set theory, the transposition may be a chromatic or diatonic transposition. Thus, if D-A-G (P5 up, M2 down) is inverted to D-G-A (P5 down, M2 up) the “pitch axis” is D. However, if it is inverted to C-F-G the pitch axis is G while if the pitch axis is A, the melody inverts to E-A-B.

Note that the notation of octave position may determine how many lines and spaces appear to share the axis. The pitch axis of D-A-G and its inversion A-D-E either appear to be between C/B♮ or the single pitch F.

Source: Inversion (music) – Wikipedia