Source: Going nutty trying to get a DHT11 to work – Everything ESP8266

Engineering and technology notes

hard reset (un-plug USB on Wemos D1) reboots into configuration mode · Issue #64 · marvinroger/homie-esp8266 · GitHub

Owner

marvinroger commented on Apr 14, 2016

This is not an expected behavior. I guess the USB is connected to a computer, can you try with a charger?

Contributor

jpmens commented on Apr 14, 2016

@sumnerboy12 I’ve just checked for you with the Homie version I’m running (Github pull pre 1.3.0): works as advertised, i.e. I can cold-boot (also via USB) and device starts publishing.

Contributor

jpmens commented on Apr 14, 2016

@sumnerboy12 it just occurs to me that I didn’t configure via WiFi, instead preferring to write the config directly to the file system. (Note the commented SPIFFS.format()which you might need to uncomment.)https://gist.github.com/jpmens/d674114400c1dd7ba169403afb7d1ea1

Owner

marvinroger commented on Apr 14, 2016

@jpmens if configuring via the API is successful, then the FS is in the exact same state as if it was written directly during flash or using your sketch, so this should not be the issue here.

Owner

marvinroger commented on Apr 14, 2016

Can you also post the debug output on the Serial monitor? There should be a message like ✖ Cannot mount filesystem. dholmen commented on Apr 14, 2016

dholmen commented on Apr 14, 2016

I’ve had the same problem with at least one of my NodeMCU’s. There are no error messages in the serial monitor, it just looks like a normal config mode boot.  sumnerboy12 commented on Apr 14, 2016

sumnerboy12 commented on Apr 14, 2016

Yes same here – there is nothing appearing on serial when it reboots

into configuration mode. I will need to have more of a play this

evening, but it is good to know this is not expected behaviour. I will

endeavour to do some more digging and report back here.On 15/04/2016 9:00 AM, dholmen wrote:

I’ve had the same problem with at least one of my NodeMCU’s. There are

no error messages in the serial monitor, it just looks like a normal

config mode boot.—

You are receiving this because you were mentioned.

Reply to this email directly or view it on GitHub

#64 (comment)

Owner

marvinroger commented on Apr 14, 2016

The configuration mode is started when the Config.load()method returns false. If you look at the sources, you will see that everywhere false is returned, there is a log message, I don’t see any codepath where this would not be the case. I might be wrong! sumnerboy12 commented on Apr 15, 2016

sumnerboy12 commented on Apr 15, 2016

after some debugging with @jpmens we discovered this was caused by Windows it seems – as soon as I unplug/re-plug the Wemo into my Windows laptop it resets the device back into config mode – if I flash the Wemo, un-plug and plug into a wall wart, it boots up fine. This can be repeated with no issues. As soon as I plug the Wemo back into my Windows laptop, it is reset and reverts back to config mode.

Very odd, but I don’t think this is a Homie issue so I will close this issue.

Contributor

jpmens commented on Apr 15, 2016

I’m confident @marvinroger knows a tonne more about these devices than we do, and can maybe say whether he’s encountered similar resets with Windows and/or whether it’s a known Windows driver issue.

Owner

marvinroger commented on Apr 15, 2016

WeMos D1 boards embed a CH340G USB serial chip. I have a NodeMCU v2, which embeds a CP2102 chip, and I had this problem once or twice, so it is way more stable. Maybe try to install this driver, if not already done. I am sorry, I can’t help more on this! But yes, definitely not an Homie issue.

sumnerboy12 commented on Apr 15, 2016

sumnerboy12 commented on Apr 15, 2016

updating to that driver seems to have resolved it – thanks a million @marvinroger!!!

Owner

marvinroger commented on Apr 16, 2016

Awesome! You’re welcome!  DavidStacer commented on Apr 16, 2016

DavidStacer commented on Apr 16, 2016

I had this problem too on a Wemos D1-mini. Updating the driver did not solve it. To diagnose this and see all the message, I connected up another USB serial port adapter. Then connected the RX from the second serial board to the D1-mini TX pin and tied GND to the serial board. I then used Termite terminal program to monitor the serial traffic.

I changed the default Homie baud rate to 74880 – that is ESP8266 default boot baud rate. This allowed me to see the ESP8266 boot up messages too.

Now I could see all of the messages. When I pulled the main D1-mini USB cable and plugged back in, the majority of the time I would see:

• SSL: no

• OTA

• Enabled: no

Flagged for reset by pin

Device is in a resettable state

Configuration erased

↻ Rebooting in config modeMy theory:

When pinMode(this->_interface->reset.triggerPin, INPUT_PULLUP); is executed, the onboard D1-mini USB Serial adapter may not let the GPIO0 pin go high right a way. If you look on the D1-mini schematic, the RTS is connected to the GPIO0 pin via resister and NPN transistor. I’m speculating that the PC driver needs to give it a command to change (high or low don’t know which).Placing a delay(50); after the Homie.setup() and before the Homie.loop(); seemed to solve the problem too but I didn’t like that as a solution.

Looking much deeper into the bounce code for the switch I found the default state is set to 0 meaning the switch is closed – requesting configuration mode. In Bounce::attach I changed it to be state=1; as the default.

I have cycled the D1-mini with the USB cable many times and it seems to have fixed the problem of going into configuration mode without pressing and holding the switch.

Owner

marvinroger commented on Apr 16, 2016

@DavidStacer so what can I do at Homie’s level? There is no way to programmatically set the default value of the state in Bounce2. So changing this line to state = 1;fixes the issue for you?Maybe I can add this in the in troubleshooting in the docs?

DavidStacer commented on Apr 16, 2016

DavidStacer commented on Apr 16, 2016

Changing that line did fix it for me because Bounce attach() sets the default to 0 but 1 would be a better default for this application. When _handleReset call is made to _resetDebuncer.read() it just returns the current Bounce::read() value. The current state is still low because update() has only been called one time, so we really are not getting a debounced reading but just the initial reading.

I think its hard to fix in Homie but maybe don’t call the _resetDebuncer.read() until the DEFAULT_RESET_TIME has passed since boot up but that is just another way of delaying. I guess we are delaying the time before getting the switch value vs. holding up the rest of the program.

I will test out that idea and see if it works.

Contributor

clough42 commented on Aug 8, 2016

I was having a similar problem and came across this issue. The solution wasn’t immediately clear, so I’m summarizing to help others who also get here and are confused: If your WeMos D1 Mini loses its configuration when you plug it into your computer with USB, it is probably erroneously detecting the RTS/DTS wiring in the WeMos as a request to reset and delete the configuration.

You can disable the reset trigger completely with Homie.disableResetTrigger() and it will stop deleting the config. If you want the reset trigger behavior, you may be able to move it to another pin. I have not attempted this.

NikosVlagoidis commented on Sep 26, 2016

NikosVlagoidis commented on Sep 26, 2016

I have the same problem but only whenever i plug it on my power bank. the problem occurred after many uses of the power bank. any thoughts?  NikosVlagoidis commented on Sep 27, 2016

NikosVlagoidis commented on Sep 27, 2016

actually Homie.disableResetTrigger() worked for my pc the first time but now does not work anywhere and i don’t know what to do

GPIO16 WOES – ESP8266 Developer Zone

glTF

glTF (GL Transmission Format) is a runtime asset delivery format for GL APIs: WebGL, OpenGL ES, and OpenGL developed by the Khronos Group 3D Formats Working Group and first announced at HTML5DevConf 2016. glTF is an efficient, interoperable asset delivery format that compresses the size of 3D scenes and models, and minimizes runtime processing by applications using WebGL and other APIs. glTF also defines a common publishing format for 3D content tools and services.

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/GlTF

160mm vs. 180mm rotor Pro/Cons?- Mtbr.com

nd here.

Otkriven misteriozan objekt u našem Sunčevom sustavu – Dnevnik.hr

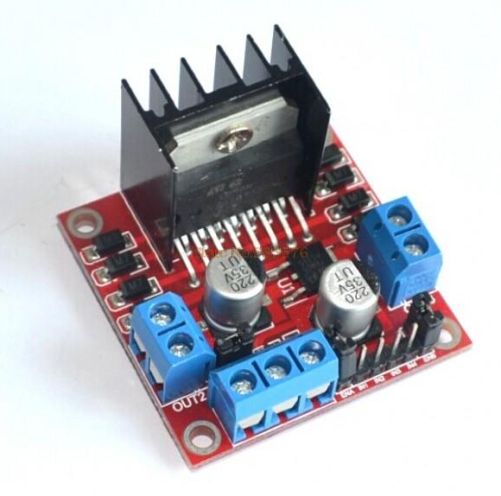

Control DC and Stepper Motors With L298N Dual Motor Controller Modules and Arduino

You don’t have to spend a lot of money to control motors with an Arduino or compatible board. After some hunting around we found a neat motor control module based on the L298N H-bridge IC that can allows you to control the speed and direction of two DC motors, or control one bipolar stepper motor with ease.The L298N H-bridge module can be used with motors that have a voltage of between 5 and 35V DC. With the module used in this tutorial, there is also an onboard 5V regulator, so if your supply voltage is up to 12V you can also source 5V from the board. So let’s get started!

Source: Control DC and Stepper Motors With L298N Dual Motor Controller Modules and Arduino

Wiznet W5100 (Ethernet Shield) Buffer Question.

So it looks like there is 8Kb of internal RX buffer on the W5100 chip… so how does one deal with reading the data faster than its coming in? If I don’t read it fast enough or too fast what happens? How do you flush the buffer on chip via client.flush()? I suspect it’s FIFO. I’m running into a situation where I am getting 8k of data posted to me and it looks like the data is being “clipped” … guess the buffer is getting filled.Looking at the W5100.c file there is mention of how the memory channels are allocated… anyone know how it’s setup to work? Full 8kb or less?

Arduino Modules – L298N Dual H-Bridge Motor Controller

Quick and simple start guide for using and exploring an L298N Dual H-Bridge Motor Controller module with an Arduino.The model in the example I am using is from Ebay. Materials needed: L298N Dual H-Bridge Motor Controller module (various models will work) Male to Female jumper wires An Arduino, any flavor. A DC power supply, 7-35vA motor that is the correct voltage for your power supply used.

Source: Arduino Modules – L298N Dual H-Bridge Motor Controller

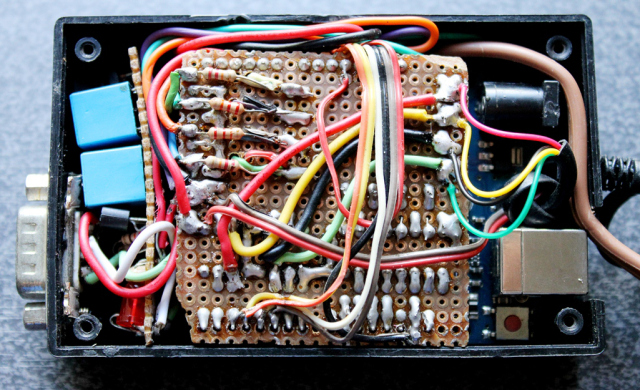

DIY Stepper Controller using Arduino | Night Sky in Focus

My first version of a stepper controller uses a 555 timer chip and a 74LS194 shift register. The tracking rate is controlled by the 555 timer chip through a resistor and a capacitor. By changing the resistance and capacitance values, the tracking rate also changes. A variable resistor is used to speed up and slow down the rotation of the stepper. Since the timing signals are controlled by analog components, the tracker suffers from issues related to the tracking rate. It usually requires ‘tracking rate adjustment’ (to match the movement of the sky) at the start of an imaging session. While it has served me for four years and used it to image some interesting targets, it is clear that an upgrade is needed.

Upon learning some basics about Arduino, I immediately saw the potential to use it as a controller for a stepper motor, the kind of motor used in devices that require precise motion control such as in many telescope mounts. I started looking at some excellent tutorials on the Internet and was able to build the simple stepper controller featured in this article.

The main advantage of using a microcontroller is that it makes it possible for the stepper controller to keep a far accurate tracking rate, unlike my previous controller that changes tracking rate with the slightest change in ambient temperature. Since it is digital, there is no need for a re-calibration at the start of every imaging session. Buttons can be placed to allow easy adjustment of the tracking speed such as to speed up or slow down the tracking rate momentarily, for easy adjustment. LEDs can be used as status indicators (e.g., current step rate).

After a few months, I have finally built a fairly simple yet reliable stepper controller that can be used to drive very small trackers, or even more advanced ones such as a telescope. And since it is built with an Arduino, it is possible to add some upgrades to it in the future.

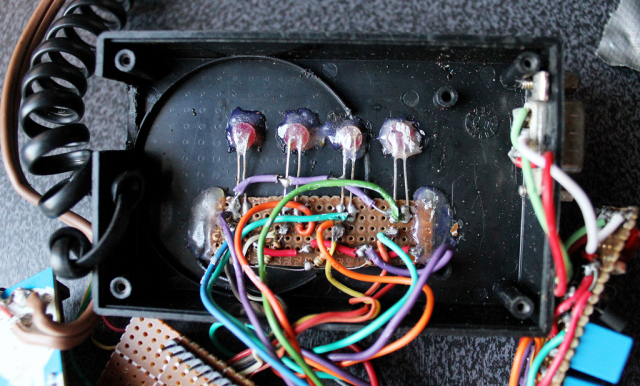

Controller for equatoral trackers such as a telescope mount with stepper motor

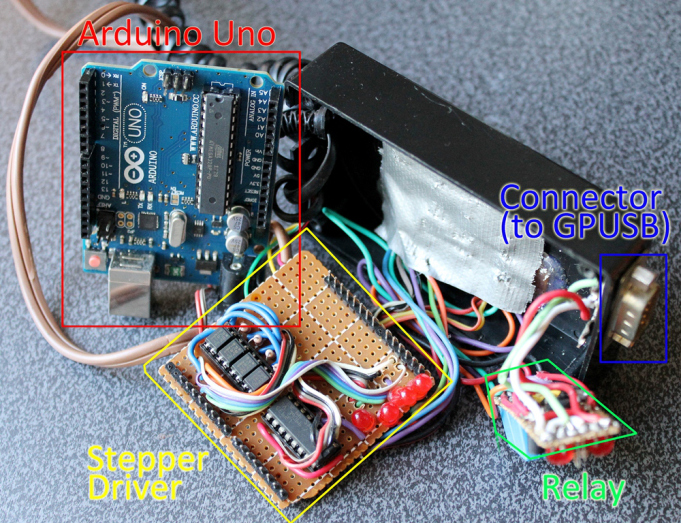

Removing the cover reveals the circuit board for the stepper driver. This circuit sits on top of the Arduino, much like a DIY shield (a circuit board that you can attach readily to an Arduino by stacking it on top of it, through the connecting pins.)

Dismantled, you can clearly see the Arduino board on the left (there are many versions of an Arduino board, in this particular project, I have used what is called an Arduino UNO). You can see the connecting pins that run vertically on the board’s left and right sides. The pins connect the Arduino to the Stepper Driver (center). The Stepper Driver is a board that holds L293D chip and some PC817 optical isolators. Some LED lights were left on the board which could come handy during troubleshooting. Also visible is some sort of a relay circuit and its connector (right), to allow a GPUSB (some kind of a module that allows a computer to talk to my telescope mount) to control the DIY Stepper Controller for autoguiding purposes (it’s a completely optional feature that I decided to include as it may come handy in the future). The use of a GPUSB, however, will be discussed in a separate article.

Components of the stepper controller. Only the Arduino Uno and the Stepper driver will be discussed in this article. The Relay and the Connector (for GPUSB) to enable a computer to send guiding signals to the stepper controller (for autoguiding purposes) will be discussed in a separate article.

Here you can see the circuit board for the LED lights and the four push-button switches.

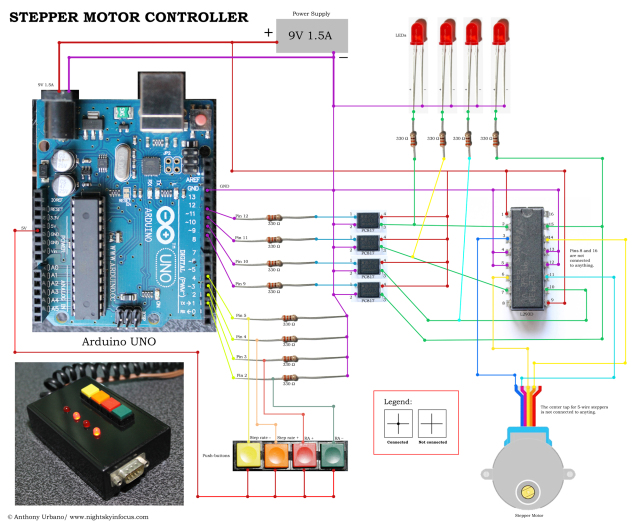

To build this DIY Stepper Controller, you will be needing some basic understanding of electronic circuits. The diagram below illustrates how the parts will be put together.

To view a larger image, click here. Circuit diagram for the Stepper Motor Controller. An Arduino Uno is used to provide pulses for the L293D H-bridge through optional PC817 opto-isolators. The circuit can drive both bipolar and unipolar steppers (operated in bipolar mode).

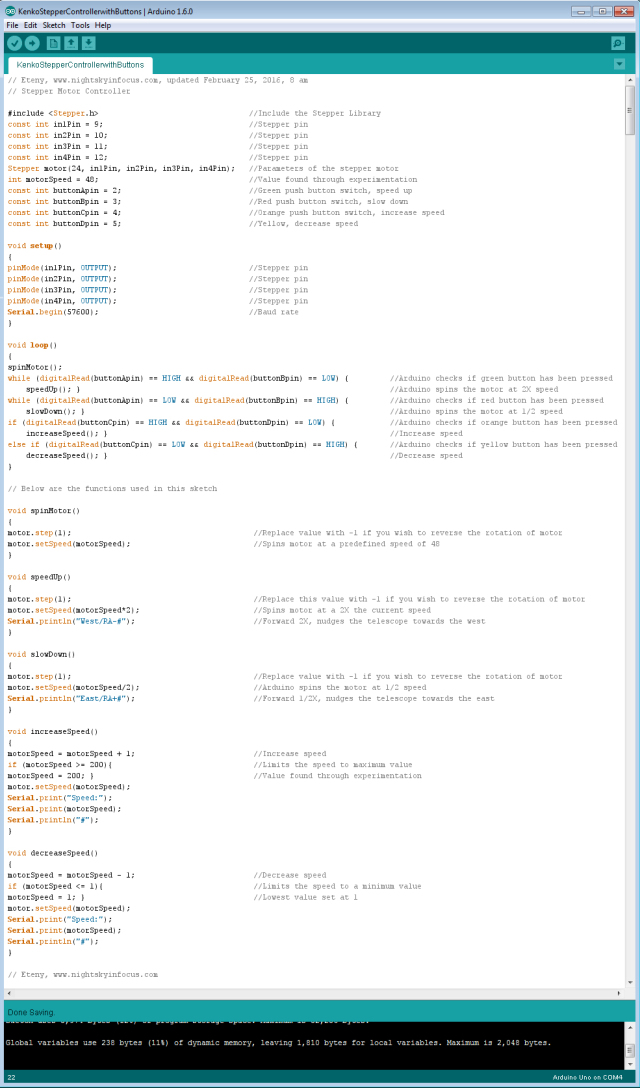

The Arduino board requires what is called a ‘sketch’. A screenshot of the sketch used in this DIY stepper controller is shown in the following photo. As you may have noticed, it is composed of lines of text with a set of instructions in it. It is a ‘program’ that you upload to the Arduino board to let it know what to do. This program is uploaded by connecting the Arduino board to a computer through a USB connection, using the Arduino Software. Learn more about Arduino. Once you are familiar with some basics, you will be able to understand how to use the sketch below.

To view a larger image, click here. Script for the Arduino stepper motor controller. For inquiries about the sketch, please send an email to eteny@nightskyinfocus.com.

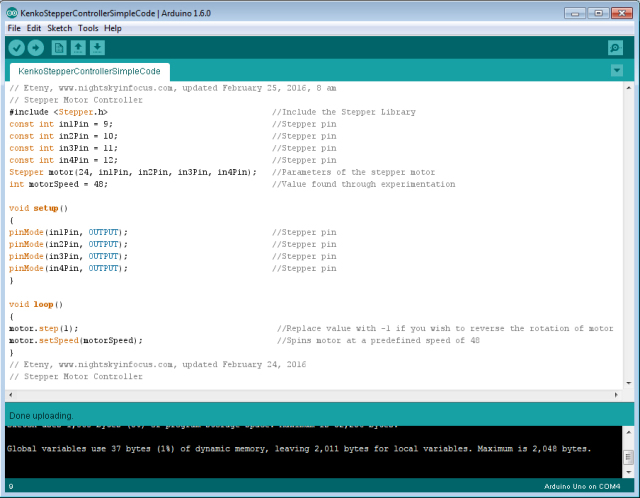

If the sketch above seems too complicated, you can try uploading a simpler sketch that can be used to spin the motor (note that this sketch does not read the buttons, it only spins the motor).

To view a larger image, click here. Script for the Arduino stepper motor controller. For inquiries about the sketch, please send an email to eteny@nightskyinfocus.com.

Once you’ve finished building the DIY Stepper Controller circuit above and uploaded the sketch to the Arduino board, you should see some blinking lights indicating that your controller is up and running and ready to track the skies!

This page is a work-in-progress. In future posts, I will describe an advanced application of the tracker such as enabling the Arduino stepper controller to receive commands from a computer through a serial connection, and perform automatic tracking error corrections (autoguiding) with a program running on a computer, such as PHD Guiding.

Visit this page for captured images and future upgrades on this project. Clear skies!

To view a larger image, click here. A 240-second test image to determine the tracker’s accuracy. The image was taken a focal length of 900 mm from a city with severe light pollution using a filter-modified Canon 450D DSLR. Tracking was guided using PHD2 Guiding software, a modified Logitech 4000 web camera, and a 400 mm focal length guide scope.

Related link:

Stepper Motor Controller (Analog)

Improvised Clock Drive Project

Source: DIY Stepper Controller using Arduino | Night Sky in Focus

Motors

This is a primer on electric motors, especially small DC motors. The information is for those who might want to know more about how the characteristics of the motor are related to the driving of a telescope and how the behavior of the motor might be affected by the type of electronic circuit used to drive it. The discussion is rather long and complex but it must be to cover the nuances of DC motor operation which are so important for some aspects of telescope operation.

Small DC motors have many favorable characteristics. They are very reliable, very strong for their size and very inexpensive. They can also be made to run on low voltages, have good electrical to mechanical conversion coefficients and are available in a immense variety of sizes and formats. They are thus used in many applications where the voltages available are only a few volts to a dozen volts. They have basic characteristics, which I will be describing, that are the result of physical and electrical laws. (No amount of advertising will change the laws of physics.) (though some will try)

The DC motor can be thought of as transducer which changes voltage and current into speed and torque. That is, electrical power into mechanical power. In the DC motor the current controls the force (or torque) and the voltage tends to control the speed. This is because of the basic relations,

FORCE = (current) X (magnetic field)

VOLTAGE = (constant) X (time rate of cutting magnetic flux)

For our purposes the constant and the magnetic field term can be considered constants which depend on the design of the motor. That is, such factors as the magnetic field strength the number of turns of wire etc. We do not need to know more about the details of the design to understand the basic behavior of the motors. We will use measured values for specific motors as examples later in this presentation.

The speed of the motor is quite proportional to the applied voltage. The reason is that the rotation of the motor creates a back voltage which counteracts the applied voltage. When these two voltages are quite different there is a substantial current through the motor which causes considerable force (torque) and the motor speeds up until the back voltage is closer to the applied voltage. When the back voltage gets quite close to the applied voltage, the current becomes smaller and the torque decreases. The motor runs at a speed where all these factors are in balance. That is, where the electrical power delivered to motor is about equal to the power absorbed by the load. Because of the resistance of the windings in the motor some power is lost to heat. So the electrical power exceeds the mechanical power by some amount. In large motors the efficiency can be well over 90%. In very small DC motors, the efficiency might be as low as 50%.

From this behavior we see that to control the speed of the motor, the voltage applied to the motor should be controlled. When this is done the stability of the motor shaft speed is stable. If the motor is loaded mechanically it slows down, the back voltage decreases and the current increases thus increasing the torque to handle the higher load. This mode of operation is generally used when the load is light and the motor shaft is turning rapidly.

The torque of the motor is proportional, as seen from the basic equations, to the current through it. If a fixed current is applied, to the motor it tends to yield a fixed torque. If the mechanical torque is greater than that available from the motor, the motor stalls. If the motor has excess torque it accelerates the load. Eventually the back voltage will become great enough to modify the current to the motor. But this will not happen rapidly because a current source, i.e. one with high resistance does not like to have its current change. It will resist the change until the value of the internal voltage is reached.

The point is that the value of the current is critical. Too little current, no motion, the motor stalls. Too much current and the motor tends to run up to an excess speed. Current and the torque it produces are very important when the motor is operating and very slow speed somewhere near stalled operation in a mechanical system. This is particularly true for systems with significant stiction. (STICTION is the tendency of mechanical loads to require starting forces that are larger than running forces. Most mechanical system have significant stiction.)

The above is actually slightly more complicated because any voltage is applied to the motor through some resistance. The resistance of the motor itself is a part of the total resistance and the resistance of the source voltage is the other part. The source resistance is called “the source resistance.” (surprise) (The Thevenin resistance to EEs) The motor resistance results in heating of the motor and is thus kept as small as possible within the design parameters of the motor. The voltage and current supplied to the motor can be easily measured. The speed and the torque of the motor can also be measured if suitable instruments are available. (I made a small dynamometer to do this.)

From the above discussion we see that for a typical DC motor, torque is high at zero speed and decreases as the speed increases. The torque tends toward zero as the speed tends toward some maximum. In order to do a motor load design, a graph of this curve, the speed torque curve, is made. This curve is repeated for different voltages. The speed torque curve of the mechanical load can also be plotted on the same graph. Where the two curves cross is a stable operating point. This graphical solution to problems is a very common design technique. The torque required to drive a mechanical load generally increases as the speed or often the square of the speed. For most mechanical loads there is a significant amount of stiction. After the mechanical system comes øunstuckÓ, then inertia and friction take over. Finally at some constant speed the torque must overcome the steady state losses in driving the load. If the mechanical curve intersects the motor curve where the motor curve is changing steeply, a very stable speed is obtained. This situation is usually considered good since the final speed is stable.

A DC motor is very often used for loads with stiction because its torque is highest at zero speed and that is where the stiction is dominant. A DC motor will can be depended on to drive the mechanical load if it can get the load started. In a design, we must be sure the starting torque of the motor will always be greater that the stiction in the mechanical system. Since the dynamic mechanical load is smaller than the stiction, the load will be driven to some final stable speed.

If there is a lot of resistance in series with the motor due to its own resistance or due to a resistance placed in series with the voltage source, the current becomes electrically limited. It is said that the motor is being current driven. If the maximum current in the current driven mode is not large enough, the motor will not turn at all. It will be stuck on the mechanical stiction of the mechanism. On the other hand, if the current is large enough to get the motor started the motor will speed up dramatically until it reaches some speed determined by the electrical torque available and the mechanical torque required. Current drive is not a good operating mode because the electrical speed torque curves with current drive and the mechanical speed torque curves intersect at a steep angle and the final speed is not clearly defined. This speed depends very much on the mechanical load which is not very stable and operation is thus not at a stable speed. For stable speed, the motor should be voltage driven.

This complicated discussion is to demonstrate that it is not a good idea to use a series resistor to control the speed of a motor. It is a better idea to change the voltage of the source to do this while keeping the series resistance as low as possible. It is a bit more complicated to change the voltage and keep the resistance in the circuit low than to simply use a series resistor. But with proper design it can be done. While I am, unfortunately, not privy to the actual circuits used in most telescope and focus drives, I suspect that the motors which behave erratically have speed controlled by simply inserting a resistor. This is the wrong way to do it.

Manufacturers do not make it easy to analyze their designs. I can get the circuit for almost any television, amplifier or other piece of electronic equipment made anywhere in the world. But some manufacturers are simply not cooperative in these matters. Reverse engineering is required and it is very time consuming. Never-the-less, I will try to discuss and evaluate several actual electrical and mechanical designs including applications to telescope drives.

Small DC motors, like other motors, are not described in a very uniform way by their manufacturers. In many motor catalogs, only the rated voltage and a high speed limit are given. In some cases the power consumption is given and in some the current is given and in some the torque is given. The specifications are a hodge-podge of information much of it useless. So design is a tricky business. In order to do a design of a telescope drive system we need to know several very specific properties. They are, more or less in order of importance: the stalled torque, the stalled current, the resistance of the motor windings, the voltage rating, the running torque at some speed and a few other things of course like the dimensions, shaft configuration and so forth.

We also need to know a few things about the mechanical system that is to be driven. This is especially the speed of the shaft under normal conditions and the torque required to drive the system. The speed required will usually be the speed of the worm that drives the main gear for sidereal rate. One complication is that both Dec and RA drives will also often require driving at a slew rate which is as much as one thousand times sidereal rate. This factor complicates the overall design but does not necessarily change the conditions required for the steady sidereal rate drive system. (nor the Dec drive for that matter)

The motor shaft and the worm shaft rates usually will be different by factors of a few dozen to several hundred times. In the LX200 drive the factor is 60. Thus a gear reduction cluster is required. This can be obtained in many ways. Everything from another worm type reduction gear, planetary gears or sets of simple spur gears have been used. In the LX200 a simple set of four metal/plastic spur gears is used. These gears are not very high precision and are in my opinion a very weak link in the mechanical design of the drives.

Some small DC motor characteristics are in the following ranges. Motors with voltage ratings of 12 to 18 volts have typical torque ratings of 1 to 5 oz.in. per ampere. These motors have typical resistances of 4 to 10 ohms. Thus one might expect stalled currents of up to 3 to 5 amperes. The lowest values give a power dissipation of 36 watts and the highest 90 watts. These small motors which have a size of about 1″ dia. and 2″ length or less cannot sustain such power dissipation for more than a few seconds. Thus it is very important to design the system so that it does not stall and/or fuse it to protect the motor and power driver devices. For the brief time that it survives, the DC motor will put out its best effort to break stiction in the mechanical system. But because of saturation of the iron in the motor it will not put out the torque estimated by linear extrapolation.

The LX200 motor has a torque of 1.55 oz.in. per ampere from measurements made with my mini-dynamometer. (this is for only one motor sample and may vary somewhat for other samples) It has a resistance of 4.5 ohms. A practical dissipation for a few seconds is about 10 watts. This dissipation heated the windings enough to increase the resistance to 5 ohms after 5 seconds. I felt this to be a safe maximum dissipation but that more would damage the motor.

Thus a safe stalled torque is about 2.33 oz.in. These numbers seem to be in the low end of DC motor specifications that I have found but are still within reason. The motor is only 3/4″ dia. by 1″ long. It is a very tiny motor. Other motors in this class that I have looked at have similar characteristics. The motor would probably put out as much as twice this torque for brief periods but I felt the heating of the motor would be excessive.

The torque is translated by the gear box to the worm shaft through a 60 to 1 gear ratio. Thus the torque at the worm shaft should be about 140 oz.in. depending how hard the motor is pushed. This assumes no losses in the gear train which is of course very optimistic. The torque at the worm shaft is fairly high considering the size of the system and it should work satisfactorily. . That this is the case is clear from the relatively good success the design has provided to many users. The torque is additionally amplified by the worm to gear interface taken as an inclined plane. I have measured the geometry of this interface and found the lever ratio to be 15. The force at the approximate 3 inch main gear radius is about 2097 oz.in. This is effectively 2.74 ft.lb. at the telescope optical tube.

We know that the friction on the Dec drive is somewhere between 0.5 and 1 ft.lb. so there is enough torque left to drive a significant unbalance on the optical tube. We do know that occasionally there is mechanical binding of the Dec drive. Mechanical binding at any place in the chain that transfers motor rotation to telescope tube motion takes a large toll on the available torque. At slow, sidereal, rates we must assume the mechanical system is going in and out of stiction constantly. There is thus a slightly jerky motion due to the rapid and non-linear changes in the stiction/friction coefficients. This causes rapid fluctuations in the torque required to move the mechanical system. It may be these fluctuations that are causing the very tiny vibrations that I have measured with a geophone and that have been reported by several observers.

The stiction in the RA main drive shaft is small because of the ball bearings in the mount. This means that most of the torque generated by the drive is available to move the fork in RA. The RA drive is well known to work much more reliably than the Dec drive in these instruments.

This analysis of the LX200 drives is quite approximate. It is rather satisfying to see the reasonable numbers appear in the analysis. The numbers show that the design is basically sound. It works fairly well as it should. The analysis also points out that the drives are by no means over designed in terms of motor strength. The mechanical system must be keep tuned up, clean, balanced and the like. I have never had problems with the drives on the 8″ LX200 Problems with the 10″ have been minimal and traced to a breakage in the drive rather than a fundamental design problem. With the 12″, the problems with the Dec drive have been more numerous in my experience. I feel that the size and strength of the drives on the 12″, which are identical to those on the smaller telescopes, are much more marginal.

Some thoughts on the design of a strong precision drive will appear on this WEB site soo

Source: motors

Aeon nox change skin

Source: Aeon nox change skin

As soon as I unplug the USB cable and re-connect, the device goes back into configuration mode.