Month: March 2017

Simple Arduino and HC-SR04 Example

My Talking Tom – Android Apps on Google Play

Amazon.com: EXP GDC Laptop External PCI-E Graphics Card: Computers & Accessories

Rudolf Diesel

Rudolf Christian Karl Diesel (German: [ˈʁuːdɔlf ˈkʁɪstjan ˈkaʁl ˈdiːzəl]; 18 March 1858 – 29 September 1913) was a German inventor and mechanical engineer, famous for the invention of the diesel engine and his mysterious death. Diesel was the subject of the 1942 film Diesel.

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rudolf_Diesel

linux – Unmount a nfs mount where the nfs server has disappeared – Server Fault

Force unmount of NFS-mounted directory

I have an NFS-mounted directory on a Linux machine that has hung. I’ve tried to force an unmount, but it doesn’t seem to work: $ umount -f /mnt/data $ umount2: Device or resource busy $ umount: /mnt/

Shortcut for Full-Screen Mode (Microsoft Word)

Want to get rid of almost everything on the screen except your document? Here’s how to easily maximize what you see. (Tips.Net)

Arduino Projects: How to write a GOTO telescope mount controller

Writing an Arduino GOTO telescope mount controller

Many people ask me to give them the code for my Arduino controlled GOTO telescope. I do not do this for two reasons.

- Arduino is about sharing knowledge. Giving you the source code will do nothing except cause you to share a lot of problems with me, which I do not have time to answer.

- The code is not written in a sufficiently formal style to withstand being shared. It has ended up being rather bespoke to my Arduino controlled telescope, and would require various amounts of refactoring for different drive setups, e.g. using stepper motors instead of DC motors.

However, whilst I am not handing over the complete code, I will be delighted to aid and guide anybody creating their own Arduino telescope system. The purpose of these notes is to provide one possible route to a complete working Arduino controlled telescope

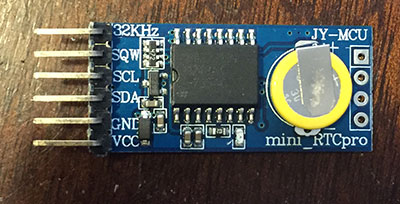

It all starts with time

The first thing to do is get a real time clock working on your Arduino. There are many real time clock modules out there on the internet and many guides on how to use them. You might even already have one built in. Make sure you have a reasonably accurate one. Go forth and do that. Make sure you can get the current time out of the RTC module and set the time.

Why do we need a real time clock for an Arduino controlled telescope?

This is the core of the telescope GOTO project. Your PC/planetarium software is only going to tell the Arduino the coordinates of the target in celestial coordinates. The Arduino GOTO code needs to work out where in the sky to point given the location, date and time. To do this, it needs to start by you getting an understanding of Local Sidereal Time.

Celestial coordinates for the Arduino GOTO.

You need to understand how RA/Dec works, what LST means and what Hour Angle means. There are countless pages on the Internet covering these subjects, but here is my take on it.

Celestial objects and the sky in general requires a coordinate system so we can locate targets in a format which is universally understood. On the surface of the Earth we use latitude and longitude. In the sky we use Right Ascension (RA) and Declination (dec). RA & Dec are analogous to latitude and longitude. RA is the East/West component (i.e. longitude) and declination is the north/south component (i.e. latitude). 90 degrees declination is roughly where Polaris is, and 0 degrees declination is on the celestial equator – an imaginary line running roughly where the zodiac constellations are.

RA, for reasons which will become clear, is measured in hours. 0h to 23h 59mins. One hour is about 15 degrees. But where does RA start? We are familiar with longitude starting at Greenwich in the UK and increasing eastwards. RA also has a zero point. It is somewhere near Pisces. It has all sorts of names and meanings which do not concern us.

So we have our coordinate system. Stars and other non-solar-system bodies can have a permanent RA/Dec which everybody can understand. Taking Regulus in Leo as an example, it is at RA = 10h 08m and Dec = 12deg 27’. Right now, 10am on the 27th July from the UK I would have to point fairly low in the east. But by later today I would need to point down in the west. Furthermore, if I lived in a different location the position in the sky would be completely different. If I lived on the equator then Regulus would be much higher in the sky.

Regulus’ RA & Dec never changes (well not much) but its apparent position in the sky various with time and location.

Enter local sidereal time (LST). Every day, from your location, the RA zero point (that spot in Pisces) will transit – i.e. be in the sky exactly south of here. Clearly this varies with the time of year and the time of day. So we define 00:00 LST to be this instant. The calculation of LST from current date, time and location is a complex approximation, found here. Please note that LST will usually appear very different to your normal local time. Right here and now it is 14:57 local time, but my LST clock says 10:14.

Now examine a telescope. The telescope must be equatorially mounted. The RA axis of the mount points at Polaris. Clearly we can move this shaft to any angle. This is called Hour Angle. If I wanted to point the telescope due south I would put the axis at zero degrees (Hour Angle zero). If I wanted to point at the horizon east or west, then it is +/- 90 degrees.

The hour angle of a star (as discussed above) depends on time and location. LST also depends on time and location. The RA of a star is fixed. The final magic bit of the puzzle is to say that the required Hour Angle of the telescope mount RA shaft is, HA = LST- RA.

For example, Regulus is at RA = 10h 08m. When the local sidereal time (LST) is 10:08, Regulus will be due south, transiting. So we would drive our telescope RA axis to the zero degrees position.

In a few hours’ time, when my LST clock reads, say 15:26, I perform the sum, HA = LST-RA = 15:26-10h 08m = +05:18. We are still in “time” here. Convert to degrees x15 so Ha = 79.5 degrees. Again, this is the angle at which I place my RA axis.

Here is another example

At the bottom in the taskbar you can see the RA of arcturus (which is due south) is almost the same as the LST

That is all, all that there is to it.

There is declination as well, but (pier flips aside) that is just a case of setting the telescope declination axis to the same value in degrees as the objects declination.

So getting back to the Arduino

As I said above, the first thing to do add LST calculation to the Arduino. Before you can do this you will also have to program it to remember your location (either store latitude and longitude in EEPROM or get it from a GPS). Whilst you are at it, store the elevation although you only need that for refraction calculations, which your planetarium software should handle.

Then write code to calculate LST, either work it out yourself or follow my LST instructions.

Now we must turn to ASCOM

Next I recommend getting the ASCOM toolchain up and running. You need a copy of Visual Studio, and you need to download the developer components from the ASCOM website. I’m not going to waffle on about creating ASCOM drivers, I covered it all in my video here and here.

Create a telescope driver and link it up to talk to your Arduino via serial. Now start implementing some of the simple properties such as location and time. You will need to invent your own protocol for talking between ASCOM and the Arduino. Nobody else is going to see it.

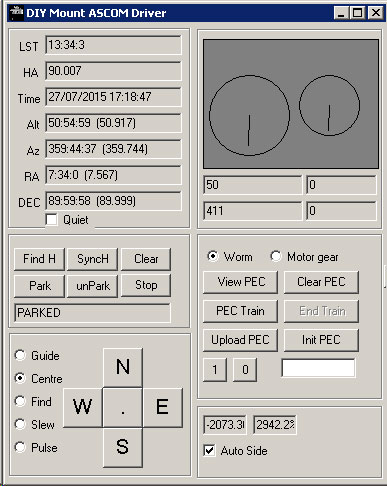

Here is an early stage of my system.

Some properties in the driver must be implemented, and the ASCOM Conformance checker can be used to validate the driver.

My suggestion is that you code some variables into Arduino which hold the current and target coordinates, and implement the various ASCOM slew methods and properties and basically make yourself a pretend telescope. Just the Arduino and the real time clock – not connected to a telescope mount. You will probably also want to implement the Altitude and Azimuth ASCOM driver properties – although it is up to you whether you do this in the ASCOM driver or in the Arduino. I did it in the Arduino.

You should then be able to connect your planetarium software to your new ASCOM driver and use GOTOs to slew around the sky. The ASCOM hubs, e.g. POTH are very good for this.

Extend the Arduino side of it so it is calculating the shaft angles required as well – i.e. implement all the HA = LST-RA stuff.

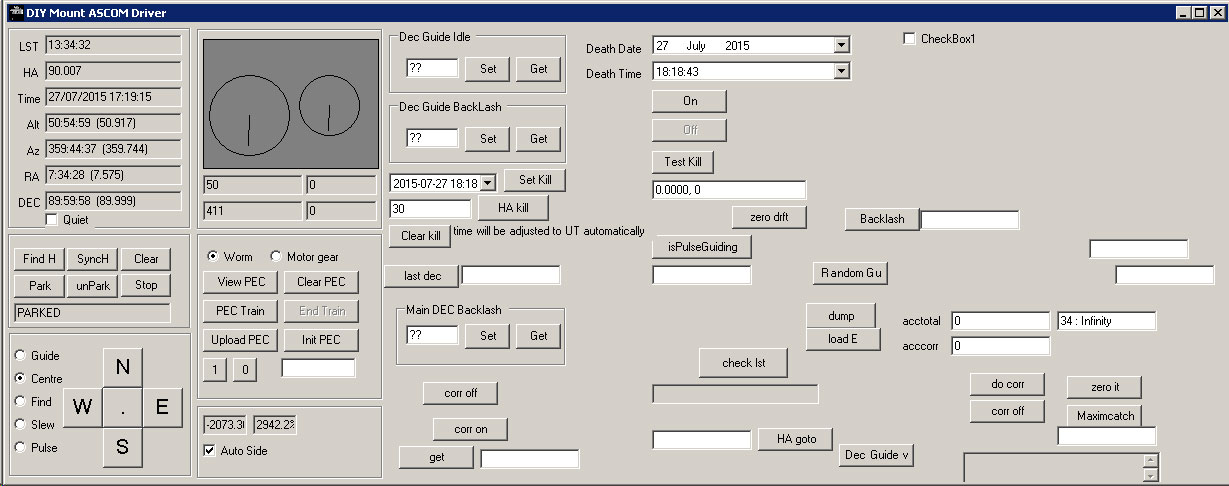

ASCOM kitchen sink window.

ASCOM tell you not to provide a popup window in your driver that has loads of buttons and the kitchen sink.

However, the only thing on your PC connected to Arduino is the ASCOM driver, and you are doing to want to be able to push a lot of non-standard commands down to the Arduino alongside the ASCOM stuff, so add a control panel window to the driver which you open when the connect property of the driver is set. You can put whatever you like on this window. Mine looks like this, although hidden from view (on the right) you can see all many of experimental test buttons and so forth.

Now you are going to need some motors

I don’t really care if you are using stepper motors or DC motors with encoders. I will talk about “encoder ticks” but this could quite easily mean stepper steps if you are doing it that way.

The most important function of a telescope mount is to track the sky at the correct speed. This means keeping the Declination axis still and slowly and smoothly moving the RA axis. By now you have probably come across the concept of a sidereal day, 23.9344696 hours. The RA Axis of our telescope mount needs to move at 1 revolution every 23.9344696 hours. So the next task is to go and setup your gears, motors, power supplies and controllers and get the Arduino running the motors, and advancing the motor smoothly at the correct speed for sidereal tracking.

How do we know the correct motor speed for sidereal tracking? In my case, I have 360 tooth worm gears. So I need to turn my worm once every 239.34 seconds . My motor has a 30:1 reduction output gearbox. So the motor spindle needs to turn at one rev every 7.98 seconds, or about 7.5rpm. My motor has 2048 tick encoder, so the motor needs to run such that the encoder is doing 1 tick every 3.8 microseconds. Or about 256 ticks per second.

But that is just my situation. Your motors and gears will be different. The goal is to implement a PID controller or somesuch that runs the motor at the correct speed for sidereal tracking.

The choice of motor and gears is critical. In my case the motor has a max speed of around 5000rpm. This is about 83 revs per second. The output gearbox, 30:1, moves at 2.7 revs per second. Therefore my max slew speed is 2.7 degrees per second (360 tooth worm remember). Motor and gear choice is a balance between being able to run at sidereal speed and having a healthy maximum slew speed.

At the slewing end, anything slower than 2 degrees per second slewing is a bit tedious. At the tracking end… well, you need the encoder resolution sufficient to run the motor smoothly at the low tracking speed. Or in the case of stepper motors, you can’t exactly advance the scope at one step per second as this will appear a little jerky.

The telescope mount will spend a lot of time running at sidereal speed… so it is important to get right.

Hook up your motor to the telescope mount and manually (PUSH-TO) move the scope to point at a star… if you’ve got the sidereal tracking correct, then the star won’t move much.

Drive the motors for manoeuvring

Now you have your Arduino running the motors smoothly at sidereal rate, you need to add the ability to run the motors a little faster – for making small adjustments to the scope position, e.g. to centre a star. You can implement 256 different speeds for the user to selected from if you wish, but don’t. Meade had this one right, you only need 4 speeds. Slew speed, find speed, centre speed and guide speed. For me, slew is top speed, find rate is about 64x sidereal and centre is about 24x sidereal. Guide is half sidereal.

These speed options are more than enough for anybody.

Or do it completely differently – it is entirely up to you.

You will have to dig into the parts of the ASCOM telescope mount driver that deal with Axis rates and MoveAxis methods. There are plenty of ASCOM client tools which allow you access to NSEW controls to steer the telescope around the sky.

It isn’t quite this simple of course. If I am sidereal tracking and need to move north at FIND speed, then I need to power up the Declination motor, but I can’t stop the sidereal rate on the RA axis. Also, if the RA axis starts moving and is then stopped, it must not stop entirely, but smoothly transition back to sidereal rate.

Moving to the right shaft angle: GOTO.

Once motors and gearing are decided and setup, it is a case of simple arithmetic to move the shafts to any particular angle. Using the bit of celestial coordinates information about, it is then straightforward to implement GOTO. Well, nearly. What happens is something like this.

- First the real time clock module is consulted by the Arduino to get the current local time.

- Arduino then uses the known longitude of the observatory to calculate the local sidereal time.

- Knowledge of the target RA is then used to find the required Hour angle.

- The required hour angle and declination are then used to calculate the required shaft angles.

- There are around 80000 encoder ticks per degree – so we can find the required encoder tick target

- Signals are then sent to slew the motors at full speed until the required encoder tick count is reach, slowing down and stopping at the correct place

However, the “correct place” is constantly changing. If the slew takes 10 seconds, the initially calculated position will be wrong by a couple of arc minutes. So you have to keep re-evaluating LST and the required shaft angles and moving a bit more until the correct place is reached.

Flipping the pier

Oh this is the worst part. Go and read the ASCOM documentation about pier flips and side-of-pier calculations. It will make your head hurt. Unless you hav a fork mount, in which case forget it.

As you will know if you own a German equatorial mount then the declination axis sometimes has to be rotated 180 degrees. What this means to us it that depending on that part of the sky you are looking at, you may need your declination shaft angle to be 180 degrees out otherwise when you move from east to west you will end up pointing at the ground.

Also remember that for every position in the sky there are two possible configurations for the mount. We are most familiar with this when doing a meridian flip. E.g. I can have the scope like this

Or like this

And both are pointing at the same azimuth, but the shaft angles are all 180 degrees out.

Both are perfectly valid. More amusingly we can point somewhere over in the west with either of these configurations

One is less useful than the other. Most mounts would crash doing the right hand version. When doing a GOTO you need to automatically choose the shaft angles that yield the correct angles for the better of the two solutions.

However, consider this telescope position.

You don’t want to have the mount pointing like this as a result of a normal GOTO, but in some situations it is actually desirable. On my driver window above you can see a little “Autoside” tickbox. This allows to me override the automatic selection of shaft angles and GOTO in to this odd position.

The purpose is to avoid a meridian flip. For example, at 9pm in early January, Orion is in the south-east and about 2 hours from transit. If I “wind” the mount back into the above position, I can start imaging Orion in the southeast, and keep tracking it without stopping for a meridian flip until it sets at about 4am.

I find this an extremely useful feature.

Correcting the GOTO

The next thing to do is implement a syncing function to refine the GOTO. This is all about the ASCOM driver methods SyncToCoordinates() etc.

Normally after performing a GOTO we aren’t pointing exactly where we want. Perhaps we GOTO a bright star, once the GOTO has finished, the user adjusts the position of the scope with the move buttons to the exact right position. The scope will now think we are pointing at a slightly different RA/Dec. Then we tell our planetarium software to “sync to target”. This tells the scope where it is actually pointing. The scope them must calculate offsets between where it thinks it is pointing and where it has been told it is pointing. These offsets are used for all future gotos until the next sync amends them.

Far more usefully, instead of a bright star, we simply take a photo and plate solve, and then use our imaging software (e.g. Maxim DL) to sync the scope to the solved position.

Parking

A Parking function is in the ASCOM driver. This simply slews the scope a previously defined Park position, and turns off the motors.

Autoguiding

Look up the pulseguide function in the ASCOM driver.

Future work

Other features I have implemented

- Emergency shut down

- Shutdown timer for unattended imaging

- Periodic error correction of the transmission gears (PEC)

- Local monitoring of temperature and humidity.

- Finding a home position (using Hall sensors)

After that you can do more or less whatever you wish!

Source: Arduino Projects: How to write a GOTO telescope mount controller

Kodi Community Forum – Ubuntu 14.04 – xbmc crashing

Stepper motor

A stepper motor or step motor or stepping motor is a brushless DC electric motor that divides a full rotation into a number of equal steps. The motor’s position can then be commanded to move and hold at one of these steps without any feedback sensor (an open-loop controller), as long as the motor is carefully sized to the application in respect to torque and speed. Switched reluctance motors are very large stepping motors with a reduced pole count, and generally are closed-loop commutated.

Source: Stepper motor – Wikipedia

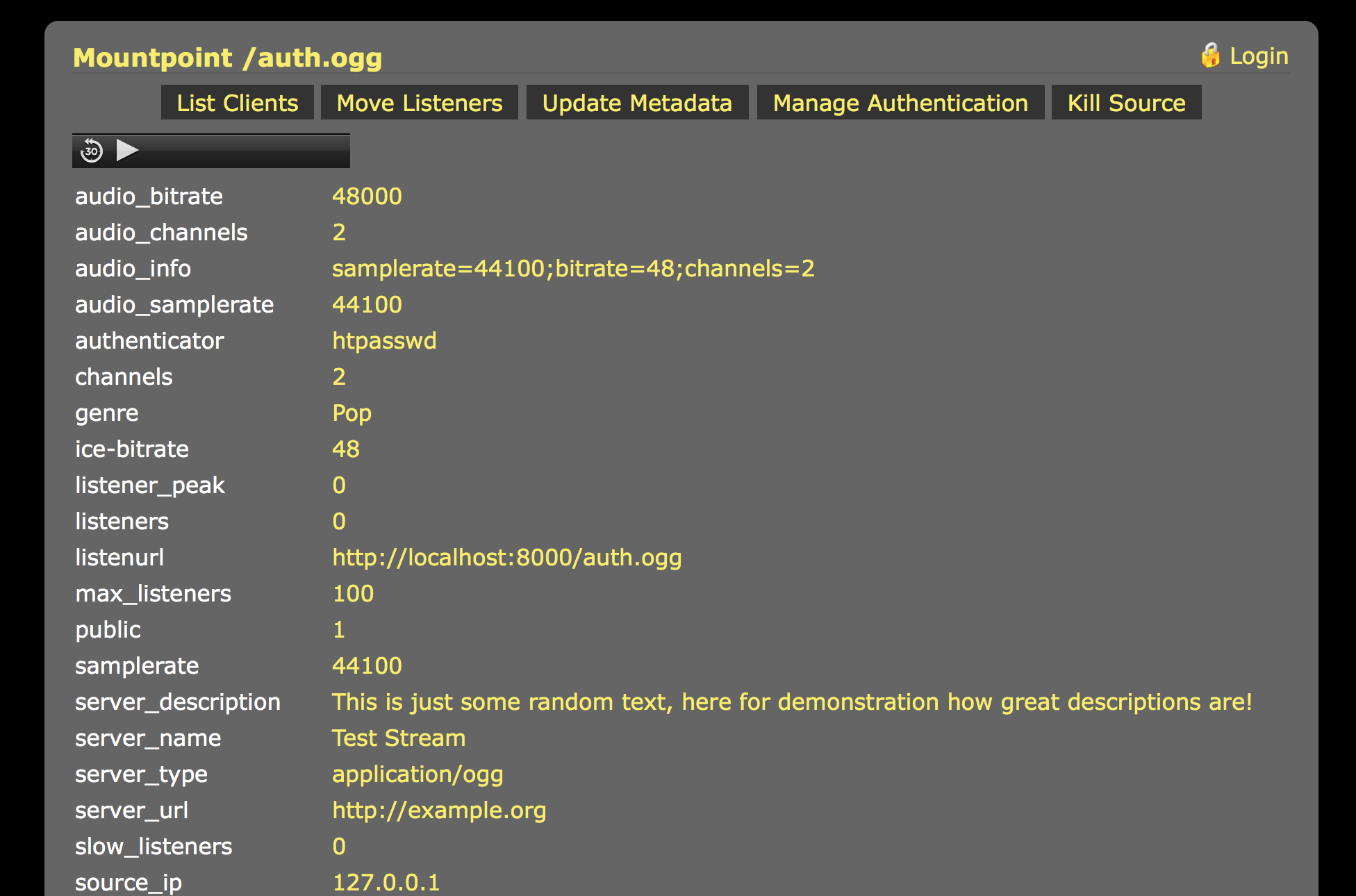

Icecast Docs — Authentication

Source: Icecast Docs — Authentication

Source: Icecast Docs — Authentication