Linus Carl Pauling (/ˈpɔːlɪŋ/; February 28, 1901 – August 19, 1994) was an American chemist, biochemist, peace activist, author, educator, and husband of American human rights activist Ava Helen Pauling. He published more than 1,200 papers and books, of which about 850 dealt with scientific topics. New Scientist called him one of the 20 greatest scientists of all time, and as of 2000, he was rated the 16th most important scientist in history.

Pauling was one of the founders of the fields of quantum chemistry and molecular biology. His contributions to the theory of the chemical bond include the concept of orbital hybridisation and the first accurate scale of electronegativities of the elements. Pauling also worked on the structures of biological molecules, and showed the importance of the alpha helix and beta sheet in protein secondary structure. Pauling’s approach combined methods and results from X-ray crystallography, molecular model building and quantum chemistry. His discoveries inspired the work of James Watson, Francis Crick, and Rosalind Franklin on the structure of DNA, which in turn made it possible for geneticists to crack the DNA code of all organisms

In his later years he promoted nuclear disarmament, as well as orthomolecular medicine, megavitamin therapy, and dietary supplements. None of the latter have gained much acceptance in the mainstream scientific community.

For his scientific work, Pauling was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1954. For his peace activism, he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1962. He is one of four individuals to have won more than one Nobel Prize (the others being Marie Curie, John Bardeen and Frederick Sanger). Of these, he is the only person to have been awarded two unshared Nobel Prizes, and one of two people to be awarded Nobel Prizes in different fields, the other being Marie Curie.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Linus_Pauling

Physics

Carl David Anderson

Quantum tunnelling

Quantum tunnelling or tunneling (see spelling differences) is the quantum mechanical phenomenon where a particle passes through a potential barrier that it classically cannot surmount. This plays an essential role in several physical phenomena, such as the nuclear fusion that occurs in main sequence stars like the Sun. It has important applications to modern devices such as the tunnel diode, quantum computing, and the scanning tunnelling microscope. The effect was predicted in the early 20th century, and its acceptance as a general physical phenomenon came mid-century.

Fundamental quantum mechanical concepts are central to this phenomenon, which makes quantum tunnelling one of the novel implications of quantum mechanics. Quantum tunneling is projected to create physical limits to how small transistors can get, due to electrons being able to tunnel past them if they are too small.

Tunnelling is often explained in terms of the Heisenberg uncertainty principle and the premise that the quantum object has more than one fixed state (not a wave nor a particle) in general.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Quantum_tunnelling

George Gamow

Willis Lamb

Robert Andrews Millikan

Deuterium

Deuterium (or hydrogen-2, symbol D or 2H, also known as heavy hydrogen) is one of two stable isotopes of hydrogen (the other being protium, or hydrogen-1). The nucleus of deuterium, called a deuteron, contains one proton and one neutron, whereas the far more common protium has no neutron in the nucleus. Deuterium has a natural abundance in Earth’s oceans of about one atom in 6420 of hydrogen. Thus deuterium accounts for approximately 0.0156% (or, on a mass basis, 0.0312%) of all the naturally occurring hydrogen in the oceans, while protium accounts for more than 99.98%. The abundance of deuterium changes slightly from one kind of natural water to another (see Vienna Standard Mean Ocean Water).

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Deuterium

Oppenheimer–Phillips process

The Oppenheimer–Phillips process or strip reaction is a type of deuteron-induced nuclear reaction. In this process the neutron half of an energetic deuteron (a stable isotope of hydrogen with one proton and one neutron) fuses with a target nucleus, transmuting the target to a heavier isotope while ejecting a proton. An example is the nuclear transmutation of carbon-12 to carbon-13.

The process allows a nuclear interaction to take place at lower energies than would be expected from a simple calculation of the Coulomb barrier between a deuteron and a target nucleus. This is because, as the deuteron approaches the positively charged target nucleus, it experiences a charge polarization where the “proton-end” faces away from the target and the “neutron-end” faces towards the target. The fusion proceeds when the binding energy of the neutron and the target nucleus exceeds the binding energy of the deuteron and a proton is then repelled from the new, heavier, nucleus

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oppenheimer%E2%80%93Phillips_process

Frank Oppenheimer

Melba Phillips

Melba Newell Phillips (February 1, 1907 – November 8, 2004) was an American physicist and pioneer science educator. One of the first doctoral students of J. Robert Oppenheimer at the University of California, Berkeley, Phillips completed her Ph.D. in 1933, a time when few women pursued careers in science. In 1935 Oppenheimer and Phillips published[1] their description of the Oppenheimer-Phillips effect, an early contribution to nuclear physics that explained the behavior of accelerated nuclei of radioactive hydrogen atoms. Phillips was also known for refusing to cooperate with a U.S. Senate judiciary subcommittee’s investigation on internal security during the McCarthy era that led to her dismissal from her professorship at Brooklyn College, where she was a professor of science from 1938 until 1952. (The college publicly and personally apologized to Phillips for the dismissal in 1987.)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Melba_Phillips

Cyclotron

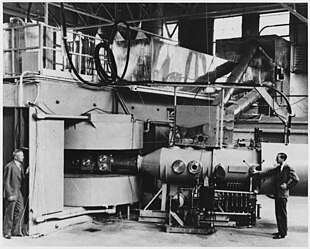

A cyclotron is a type of particle accelerator invented by Ernest O. Lawrence in 1929-1930 at the University of California, Berkeley, and patented in 1932. A cyclotron accelerates charged particles outwards from the center along a spiral path. The particles are held to a spiral trajectory by a static magnetic field and accelerated by a rapidly varying (radio frequency) electric field. Ernest O. Lawrence was awarded the 1939 Nobel prize in physicsfor this invention.

Cyclotrons were the most powerful particle accelerator technology until the 1950s when they were superseded by the synchrotron, and are still used to produce particle beams in physics and nuclear medicine. The largest single-magnet cyclotron was the 4.67 m (184 in) synchrocyclotron built between 1940 and 1946 by Lawrence at the University of California at Berkeley, which could accelerate protons to 730 million electron volts (MeV). The largest cyclotron is the 17.1 m (56 ft) multimagnet TRIUMF accelerator at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, British Columbia which can produce 500 MeV protons.

Over 1200 cyclotrons are used in nuclear medicine worldwide for the production of radionuclides.

Ernest Walton

Ernest Thomas Sinton Walton (6 October 1903 – 25 June 1995) was an Irish physicist and Nobel laureate for his work with John Cockcroft with “atom-smashing” experiments done at Cambridge University in the early 1930s, and so became the first person in history to artificially split the atom.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ernest_Walton