https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maxwell%E2%80%93Boltzmann_distribution

Month: February 2023

Rudolf Clausius

Frank Wilczek

Frank Anthony Wilczek (/ˈwɪltʃɛk/; born May 15, 1951) is an American theoretical physicist, mathematician and Nobel laureate. He is currently the Herman Feshbach Professor of Physics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), Founding Director of T. D. Lee Institute and Chief Scientist at the Wilczek Quantum Center, Shanghai Jiao Tong University (SJTU), distinguished professor at Arizona State University (ASU) and full professor at Stockholm University.

Wilczek, along with David Gross and H. David Politzer, was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 2004 “for the discovery of asymptotic freedom in the theory of the strong interaction“. In May 2022, he was awarded the Templeton Prize for Progress Toward Research or Discoveries about Spiritual Realities.

Babylon (2022)

owncloud-client not starting in Ubuntu 20.04 virtual machine

If your owncloud-client is not working in a Ubuntu 20.04 virtual machine try installing virtualbox guest additons:

sudo apt install virtualbox-guest-dkms virtualbox-guest-x11

Source: RIS – Robust Information Systems

Russell’s paradox

Configure LDAP Client on Ubuntu 22.04|20.04|18.04|16.04

Source: Configure LDAP Client on Ubuntu 22.04|20.04|18.04|16.04 | ComputingForGeeks

David Bohm

David Joseph Bohm FRS (/boʊm/; 20 December 1917 – 27 October 1992) was an American-Brazilian-British scientist who has been described as one of the most significant theoretical physicists of the 20th century and who contributed unorthodox ideas to quantum theory, neuropsychology and the philosophy of mind. Among his many contributions to physics is his causal and deterministic interpretation of quantum theory, now known as De Broglie–Bohm theory.

Bohm advanced the view that quantum physics meant that the old Cartesian model of reality—that there are two kinds of substance, the mental and the physical, that somehow interact—was too limited. To complement it, he developed a mathematical and physical theory of “implicate” and “explicate” order. He also believed that the brain, at the cellular level, works according to the mathematics of some quantum effects, and postulated that thought is distributed and non-localised just as quantum entities are. Bohm’s main concern was with understanding the nature of reality in general and of consciousness in particular as a coherent whole, which according to Bohm is never static or complete.

Bohm warned of the dangers of rampant reason and technology, advocating instead the need for genuine supportive dialogue, which he claimed could broaden and unify conflicting and troublesome divisions in the social world. In this, his epistemology mirrored his ontology.

Born in the United States, Bohm obtained his Ph.D. under J. Robert Oppenheimer at the University of California, Berkeley. Due to his Communist affiliations, he was the subject of a federal government investigation in 1949, prompting him to leave the U.S. He pursued his career in several countries, becoming first a Brazilian and then a British citizen. He abandoned Marxism in the wake of the Hungarian Uprising in 1956.

Grete Hermann

Grete Hermann (2 March 1901 – 15 April 1984) was a German mathematician and philosopher noted for her work in mathematics, physics, philosophy and education. She is noted for her early philosophical work on the foundations of quantum mechanics, and is now known most of all for an early, but long-ignored critique of a “no hidden-variables theorem” by John von Neumann. It has been suggested that, had her critique not remained nearly unknown for decades, the historical development of quantum mechanics might have been very different.

docker mysqldump

docker exec some-mysql sh -c ‘exec mysqldump –all-databases -uroot -p”$MYSQL_ROOT_PASSWORD”‘ > /some/path/on/your/host/all-databases.sql

Source: mysql – Official Image | Docker Hub

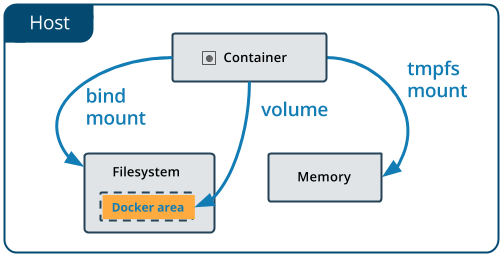

Volumes | Docker Documentation

Volumes are the preferred mechanism for persisting data generated by and used by Docker containers. While bind mounts are dependent on the directory structure and OS of the host machine, volumes are completely managed by Docker. Volumes have several advantages over bind mounts:

- Volumes are easier to back up or migrate than bind mounts.

- You can manage volumes using Docker CLI commands or the Docker API.

- Volumes work on both Linux and Windows containers.

- Volumes can be more safely shared among multiple containers.

- Volume drivers let you store volumes on remote hosts or cloud providers, to encrypt the contents of volumes, or to add other functionality.

- New volumes can have their content pre-populated by a container.

- Volumes on Docker Desktop have much higher performance than bind mounts from Mac and Windows hosts.

In addition, volumes are often a better choice than persisting data in a container’s writable layer, because a volume does not increase the size of the containers using it, and the volume’s contents exist outside the lifecycle of a given container.

If your container generates non-persistent state data, consider using a tmpfs mount to avoid storing the data anywhere permanently, and to increase the container’s performance by avoiding writing into the container’s writable layer.

Volumes use rprivate bind propagation, and bind propagation is not configurable for volumes.

Choose the -v or –mount flag

In general, --mount is more explicit and verbose. The biggest difference is that the -v syntax combines all the options together in one field, while the --mount syntax separates them. Here is a comparison of the syntax for each flag.

If you need to specify volume driver options, you must use --mount.

-vor--volume: Consists of three fields, separated by colon characters (:). The fields must be in the correct order, and the meaning of each field is not immediately obvious.- In the case of named volumes, the first field is the name of the volume, and is unique on a given host machine. For anonymous volumes, the first field is omitted.

- The second field is the path where the file or directory are mounted in the container.

- The third field is optional, and is a comma-separated list of options, such as

ro. These options are discussed below.

--mount: Consists of multiple key-value pairs, separated by commas and each consisting of a<key>=<value>tuple. The--mountsyntax is more verbose than-vor--volume, but the order of the keys is not significant, and the value of the flag is easier to understand.- The

typeof the mount, which can bebind,volume, ortmpfs. This topic discusses volumes, so the type is alwaysvolume. - The

sourceof the mount. For named volumes, this is the name of the volume. For anonymous volumes, this field is omitted. May be specified assourceorsrc. - The

destinationtakes as its value the path where the file or directory is mounted in the container. May be specified asdestination,dst, ortarget. - The

readonlyoption, if present, causes the bind mount to be mounted into the container as read-only. May be specified asreadonlyorro. - The

volume-optoption, which can be specified more than once, takes a key-value pair consisting of the option name and its value.

- The

Escape values from outer CSV parser

If your volume driver accepts a comma-separated list as an option, you must escape the value from the outer CSV parser. To escape a

volume-opt, surround it with double quotes (") and surround the entire mount parameter with single quotes (').For example, the

localdriver accepts mount options as a comma-separated list in theoparameter. This example shows the correct way to escape the list.$ docker service create \ --mount 'type=volume,src=<VOLUME-NAME>,dst=<CONTAINER-PATH>,volume-driver=local,volume-opt=type=nfs,volume-opt=device=<nfs-server>:<nfs-path>,"volume-opt=o=addr=<nfs-address>,vers=4,soft,timeo=180,bg,tcp,rw"' --name myservice \ <IMAGE>

The examples below show both the --mount and -v syntax where possible, and --mount is presented first.

Differences between -v and --mount behavior

As opposed to bind mounts, all options for volumes are available for both --mount and -v flags.

When using volumes with services, only --mount is supported.

Create and manage volumes

Unlike a bind mount, you can create and manage volumes outside the scope of any container.

Create a volume:

$ docker volume create my-vol

List volumes:

$ docker volume ls

local my-vol

Inspect a volume:

$ docker volume inspect my-vol

[

{

"Driver": "local",

"Labels": {},

"Mountpoint": "/var/lib/docker/volumes/my-vol/_data",

"Name": "my-vol",

"Options": {},

"Scope": "local"

}

]

Remove a volume:

$ docker volume rm my-vol

Start a container with a volume

If you start a container with a volume that doesn’t yet exist, Docker creates the volume for you. The following example mounts the volume myvol2 into /app/ in the container.

The -v and --mount examples below produce the same result. You can’t run them both unless you remove the devtest container and the myvol2 volume after running the first one.

$ docker run -d \

--name devtest \

--mount source=myvol2,target=/app \

nginx:latest

Use docker inspect devtest to verify that the volume was created and mounted correctly. Look for the Mounts section:

"Mounts": [

{

"Type": "volume",

"Name": "myvol2",

"Source": "/var/lib/docker/volumes/myvol2/_data",

"Destination": "/app",

"Driver": "local",

"Mode": "",

"RW": true,

"Propagation": ""

}

],

This shows that the mount is a volume, it shows the correct source and destination, and that the mount is read-write.

Stop the container and remove the volume. Note volume removal is a separate step.

$ docker container stop devtest

$ docker container rm devtest

$ docker volume rm myvol2

Use a volume with Docker Compose

Here’s an example of a single Docker Compose service with a volume:

services:

frontend:

image: node:lts

volumes:

- myapp:/home/node/app

volumes:

myapp:

Running docker compose up for the first time creates a volume. The same volume is reused when you subsequently run the command.

You can create a volume directly outside of Compose using docker volume create and then reference it inside docker-compose.yml as follows:

services:

frontend:

image: node:lts

volumes:

- myapp:/home/node/app

volumes:

myapp:

external: true

For more information about using volumes with Compose, refer to the Volumes section in the Compose specification.

Start a service with volumes

When you start a service and define a volume, each service container uses its own local volume. None of the containers can share this data if you use the local volume driver. However, some volume drivers do support shared storage.

The following example starts an nginx service with four replicas, each of which uses a local volume called myvol2.

$ docker service create -d \

--replicas=4 \

--name devtest-service \

--mount source=myvol2,target=/app \

nginx:latest

Use docker service ps devtest-service to verify that the service is running:

$ docker service ps devtest-service

ID NAME IMAGE NODE DESIRED STATE CURRENT STATE ERROR PORTS

4d7oz1j85wwn devtest-service.1 nginx:latest moby Running Running 14 seconds ago

You can remove the service to stop the running tasks:

$ docker service rm devtest-service

Removing the service doesn’t remove any volumes created by the service. Volume removal is a separate step.

Syntax differences for services

The docker service create command doesn’t support the -v or --volume flag. When mounting a volume into a service’s containers, you must use the --mount flag.

Populate a volume using a container

If you start a container which creates a new volume, and the container has files or directories in the directory to be mounted such as /app/, the directory’s contents are copied into the volume. The container then mounts and uses the volume, and other containers which use the volume also have access to the pre-populated content.

To illustrate this, the following example starts an nginx container and populates the new volume nginx-vol with the contents of the container’s /usr/share/nginx/html directory. This is where Nginx stores its default HTML content.

The --mount and -v examples have the same end result.

$ docker run -d \

--name=nginxtest \

--mount source=nginx-vol,destination=/usr/share/nginx/html \

nginx:latest

After running either of these examples, run the following commands to clean up the containers and volumes. Note volume removal is a separate step.

$ docker container stop nginxtest

$ docker container rm nginxtest

$ docker volume rm nginx-vol

Use a read-only volume

For some development applications, the container needs to write into the bind mount so that changes are propagated back to the Docker host. At other times, the container only needs read access to the data. Multiple containers can mount the same volume. You can simultaneously mount a single volume as read-write for some containers and as read-only for others.

The following example modifies the one above but mounts the directory as a read-only volume, by adding ro to the (empty by default) list of options, after the mount point within the container. Where multiple options are present, you can separate them using commas.

The --mount and -v examples have the same result.

$ docker run -d \

--name=nginxtest \

--mount source=nginx-vol,destination=/usr/share/nginx/html,readonly \

nginx:latest

Use docker inspect nginxtest to verify that the read-only mount was created correctly. Look for the Mounts section:

"Mounts": [

{

"Type": "volume",

"Name": "nginx-vol",

"Source": "/var/lib/docker/volumes/nginx-vol/_data",

"Destination": "/usr/share/nginx/html",

"Driver": "local",

"Mode": "",

"RW": false,

"Propagation": ""

}

],

Stop and remove the container, and remove the volume. Volume removal is a separate step.

$ docker container stop nginxtest

$ docker container rm nginxtest

$ docker volume rm nginx-vol

Share data between machines

When building fault-tolerant applications, you may need to configure multiple replicas of the same service to have access to the same files.

There are several ways to achieve this when developing your applications. One is to add logic to your application to store files on a cloud object storage system like Amazon S3. Another is to create volumes with a driver that supports writing files to an external storage system like NFS or Amazon S3.

Volume drivers allow you to abstract the underlying storage system from the application logic. For example, if your services use a volume with an NFS driver, you can update the services to use a different driver, as an example to store data in the cloud, without changing the application logic.

Use a volume driver

When you create a volume using docker volume create, or when you start a container which uses a not-yet-created volume, you can specify a volume driver. The following examples use the vieux/sshfs volume driver, first when creating a standalone volume, and then when starting a container which creates a new volume.

Initial setup

The following example assumes that you have two nodes, the first of which is a Docker host and can connect to the second node using SSH.

On the Docker host, install the vieux/sshfs plugin:

$ docker plugin install --grant-all-permissions vieux/sshfs

Create a volume using a volume driver

This example specifies an SSH password, but if the two hosts have shared keys configured, you can exclude the password. Each volume driver may have zero or more configurable options, each of which is specified using an -o flag.

$ docker volume create --driver vieux/sshfs \

-o sshcmd=test@node2:/home/test \

-o password=testpassword \

sshvolume

Start a container which creates a volume using a volume driver

The following example specifies an SSH password. However, if the two hosts have shared keys configured, you can exclude the password. Each volume driver may have zero or more configurable options.

Note:

If the volume driver requires you to pass any options, you must use the

--mountflag to mount the volume, and not-v.

$ docker run -d \

--name sshfs-container \

--volume-driver vieux/sshfs \

--mount src=sshvolume,target=/app,volume-opt=sshcmd=test@node2:/home/test,volume-opt=password=testpassword \

nginx:latest

Create a service which creates an NFS volume

The following example shows how you can create an NFS volume when creating a service. It uses 10.0.0.10 as the NFS server and /var/docker-nfs as the exported directory on the NFS server. Note that the volume driver specified is local.

NFSv3

$ docker service create -d \

--name nfs-service \

--mount 'type=volume,source=nfsvolume,target=/app,volume-driver=local,volume-opt=type=nfs,volume-opt=device=:/var/docker-nfs,volume-opt=o=addr=10.0.0.10' \

nginx:latest

NFSv4

$ docker service create -d \

--name nfs-service \

--mount 'type=volume,source=nfsvolume,target=/app,volume-driver=local,volume-opt=type=nfs,volume-opt=device=:/var/docker-nfs,"volume-opt=o=addr=10.0.0.10,rw,nfsvers=4,async"' \

nginx:latest

Create CIFS/Samba volumes

You can mount a Samba share directly in Docker without configuring a mount point on your host.

$ docker volume create \

--driver local \

--opt type=cifs \

--opt device=//uxxxxx.your-server.de/backup \

--opt o=addr=uxxxxx.your-server.de,username=uxxxxxxx,password=*****,file_mode=0777,dir_mode=0777 \

--name cif-volume

The addr option is required if you specify a hostname instead of an IP. This lets Docker perform the hostname lookup.

Block storage devices

You can mount a block storage device, such as an external drive or a drive partition, to a container. The following example shows how to create and use a file as a block storage device, and how to mount the block device as a container volume.

Important

The following procedure is only an example. The solution illustrated here isn’t recommended as a general practice. Don’t attempt this approach unless you’re very confident about what you’re doing.

How mounting block devices works

Under the hood, the --mount flag using the local storage driver invokes the Linux mount syscall and forwards the options you pass to it unaltered. Docker doesn’t implement any additional functionality on top of the native mount features supported by the Linux kernel.

If you’re familiar with the Linux mount command, you can think of the --mount options as being forwarded to the mount command in the following manner:

$ mount -t <mount.volume-opt.type> <mount.volume-opt.device> <mount.dst> -o <mount.volume-opts.o>

To illustrate this further, consider the following mount command example. This command mounts the /dev/loop5 device to the path /external-drive on the system.

$ mount -t ext4 /dev/loop5 /external-drive

The following docker run command achieves a similar result, from the point of view of the container being run. Running a container with this --mount option sets up the mount in the same way as if you had executed the mount command from the previous example.

$ docker run \

--mount='type=volume,dst=/external-drive,volume-driver=local,volume-opt=device=/dev/loop5,volume-opt=type=ext4'

You can’t execute the mount command inside the container directly, because the container is unable to access the /dev/loop5 device. That’s why we’re using the --mount option for the docker run command instead.

Example: Mounting a block device in a container

The following steps create an ext4 filesystem and mounts it into a container. The filesystem support of your system depends on the version of the Linux kernel you are using.

- Create a file and allocate some space to it:

$ fallocate -f 1G disk.raw - Build a filesystem onto the

disk.rawfile:$ mkfs.ext4 disk.raw - Create a loop device:

$ losetup -f --show disk.raw /dev/loop5Note

losetupcreates an ephemeral loop device that’s removed after system reboot, or manually removed withlosetup -d. - Run a container that mounts the loop device as a volume:

$ docker run -it --rm \ --mount='type=volume,dst=/external-drive,volume-driver=local,volume-opt=device=/dev/loop5,volume-opt=type=ext4' \ ubuntu bashWhen the container starts, the path

/external-drivemounts thedisk.rawfile from the host filesystem as a block device. - When you’re done, and the device is unmounted from the container, detach the loop device to remove the device from the host system:

$ losetup -d /dev/loop5

Back up, restore, or migrate data volumes🔗

Volumes are useful for backups, restores, and migrations. Use the --volumes-from flag to create a new container that mounts that volume.

Back up a volume

For example, create a new container named dbstore:

$ docker run -v /dbdata --name dbstore ubuntu /bin/bash

In the next command:

- Launch a new container and mount the volume from the

dbstorecontainer - Mount a local host directory as

/backup - Pass a command that tars the contents of the

dbdatavolume to abackup.tarfile inside our/backupdirectory.

$ docker run --rm --volumes-from dbstore -v $(pwd):/backup ubuntu tar cvf /backup/backup.tar /dbdata

When the command completes and the container stops, it creates a backup of the dbdata volume.

Restore volume from a backup

With the backup just created, you can restore it to the same container, or to another container that you created elsewhere.

For example, create a new container named dbstore2:

$ docker run -v /dbdata --name dbstore2 ubuntu /bin/bash

Then, un-tar the backup file in the new container’s data volume:

$ docker run --rm --volumes-from dbstore2 -v $(pwd):/backup ubuntu bash -c "cd /dbdata && tar xvf /backup/backup.tar --strip 1"

You can use the techniques above to automate backup, migration, and restore testing using your preferred tools.

Source: Volumes | Docker Documentation